Sea Change: As Sea Levels Rise, Can Saltmarshes Be Saved?

By Ariel Wittenberg

Saltmarsh Sparrow by Ray Hennessy. April 2, 2020From the Spring 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The photography by Jonathan Fiely in this story was made possible with support from the Robert F. Schumann Foundation, a charitable trust dedicated to improving the quality of life of both humans and animals by supporting environmental, educational, arts, and cultural organizations and agencies.

The red streaks of dawn barely penetrate the sky when Greg Shriver and his team of researchers meet in the parking lot of the Oyster Creek Restaurant and Boat Bar, preparing to head into the marsh.

It’s early August in coastal New Jersey, and Shriver—an ecology professor at the University of Delaware—is here to check in on the Saltmarsh Sparrows his graduate students have spent the summer tracking at Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge.

In one nest, a sparrow laid three eggs. But before chicks hatched, floods drowned the nest. All the eggs were lost.

Losing nests, losing eggs, and losing birds is an occupational hazard for biologists studying the Saltmarsh Sparrow. The small brown bird with striking orange markings on its face is the goldilocks of saltmarshes, so choosy about where it nests. And that could well prove fatal to the entire species as sea levels rise.

The work can get depressing, Shriver will admit later that morning.

University of Delaware ecology professor Greg Shriver (white shirt) studies the effects of sea-level rise on tidal marsh birds—particularly the Saltmarsh Sparrow. Here, he assembles his team of graduate students for their ongoing research at the Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey. Photo by Ray Hennessy.

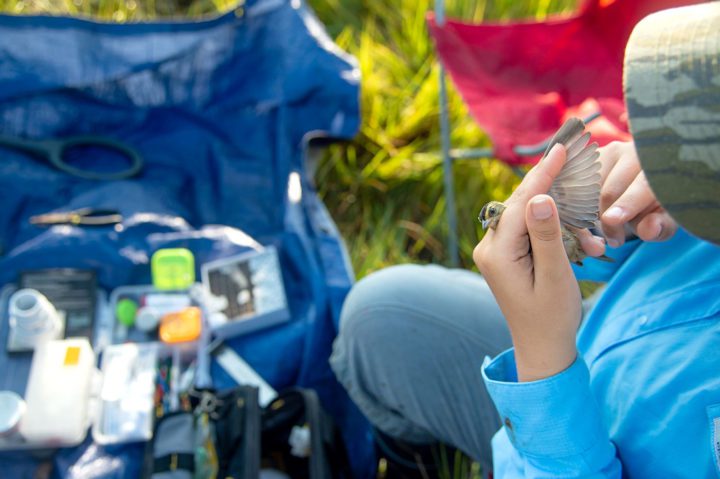

Shriver demonstrates how to delicately extract a Saltmarsh Sparrow from a mist net. Photo by Ray Hennessy.

Shriver and his team measure, weigh, and extract blood samples from captured Saltmarsh Sparrows. But he is rapidly losing new generations of his study subjects, as nests are often washed away by higher tides caused by sea-level rise. Photo by Ray Hennessy.

“For conservation biologists, this is like our whole career,” he says as he watches his graduate students measure, tag, and sample blood from Saltmarsh Sparrows caught in mist nets. “You have to be willing to accept it. We work with things that are declining and possibly going extinct.”

Saltmarsh Sparrows could be among the first extinction casualties from climate change and sea-level rise. Already, the birds’ population has declined by 75% since the 1990s—and with a current estimated 9% population loss annually, these sparrows might not make it to the year 2050.

That makes this a critical moment for Saltmarsh Sparrows, and the humans who care about them. Last fall, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture released a 144-page master plan to help save saltmarsh ecosystems with strategies to save the Saltmarsh Sparrow, as well as its fellow tidal-marsh birds American Black Duck and Black Rail, from population collapse. The venture is a regional partnership between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state governments, and nonprofits dedicated to saving native bird habitats along the East Coast.

One of the most promising strategies from the plan encourages “marsh migration” by conserving places that, while currently dry, will likely convert into wetlands as sea levels rise, potentially creating new saltmarshes to offset what’s lost. There are other strategies in the plan, too, including restoring currently degraded marshes to make them more resilient against rising tides.

But no strategy is a sure bet, and Saltmarsh Sparrows are running out of time. So, the Joint Venture advocates deploying all eight strategies simultaneously—and as soon as possible.

How much that will cost is a mystery. While some of those strategies have been used in select saltmarshes, the costs vary from site to site, and it’s not yet clear which ones will be most successful, or most necessary to save the Saltmarsh Sparrow.

“It’s a tricky system,” Atlantic Coast Joint Venture coordinator Aimee Weldon says of the saltmarshes, “and we’ve never really had to fight this battle before.

“Is this going to work or not? We really don’t know. But you can’t hold the sea back, so we have to figure it out as we go along.”

A Sparrow-Sized Indicator of Saltmarsh Health

Saltmarsh Sparrows are interesting study subjects for ecologists for a number of reasons—they have a haunting whispered song, they aren’t territorial, and they don’t form mating pairs, with males roaming around the marsh to breed with females wherever they can be found. (Shriver calls them “the most promiscuous bird.”)

What’s more, they are the only songbird species with a life cycle entirely dependent on the saltmarsh, and they are only found between New England and Florida. That makes Saltmarsh Sparrows what’s called an “indicator species” for the status of all tidal-marsh habitat on the East Coast.

“They are the canaries in the coal mines for saltmarsh ecosystems,” explains Jennifer Walsh, a postdoctoral fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who has studied how these birds evolved to fit their habitat. “If Saltmarsh Sparrows go extinct, it means we’ve lost our marshes, and [saltmarshes] have a lot of value for people beyond just the organisms that live in them.”

Indeed, coastal marshes are important nurseries for fish and shellfish, including those that are harvested by a commercial fishing industry worth billions. Saltmarshes also absorb floodwaters and tidal energy from raging seas during storms, helping to stabilize shorelines and protect the 40% of Americans who live in coastal communities.

“If Saltmarsh Sparrows go away, we’ve lost something a lot bigger than just the birds,” Walsh says.

Saltmarshes on the East Coast are often sandwiched between human communities and the sea. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge is no exception. When Shriver and his team slip into the soggy marsh from a dirt road, everyone suddenly concentrates on their rain boots, gingerly stepping on the stands of greenish-yellow cordgrass that signal solid ground. As they walk, they trade stories about times they miscalculated, fell into tidal creeks, and got stuck in chest-high brown, salty muck.

Saltmarsh Sparrows live in the high marshes, a sliver of tidal wetlands that flood only twice a month during the highest tides. These sections of the marsh are higher in elevation than others, meaning they are often closest to human development, with homes, telephone poles, and other signs of civilization visible at the marsh’s edge.

Looking back toward the sea, the cordgrass seemingly stretches on forever, punctuated only by tidal creeks. The elevation of the marsh gradually decreases until it reaches the ocean. Unlike the high marsh, those lower areas flood twice daily with the high tides, making them completely different habitat.

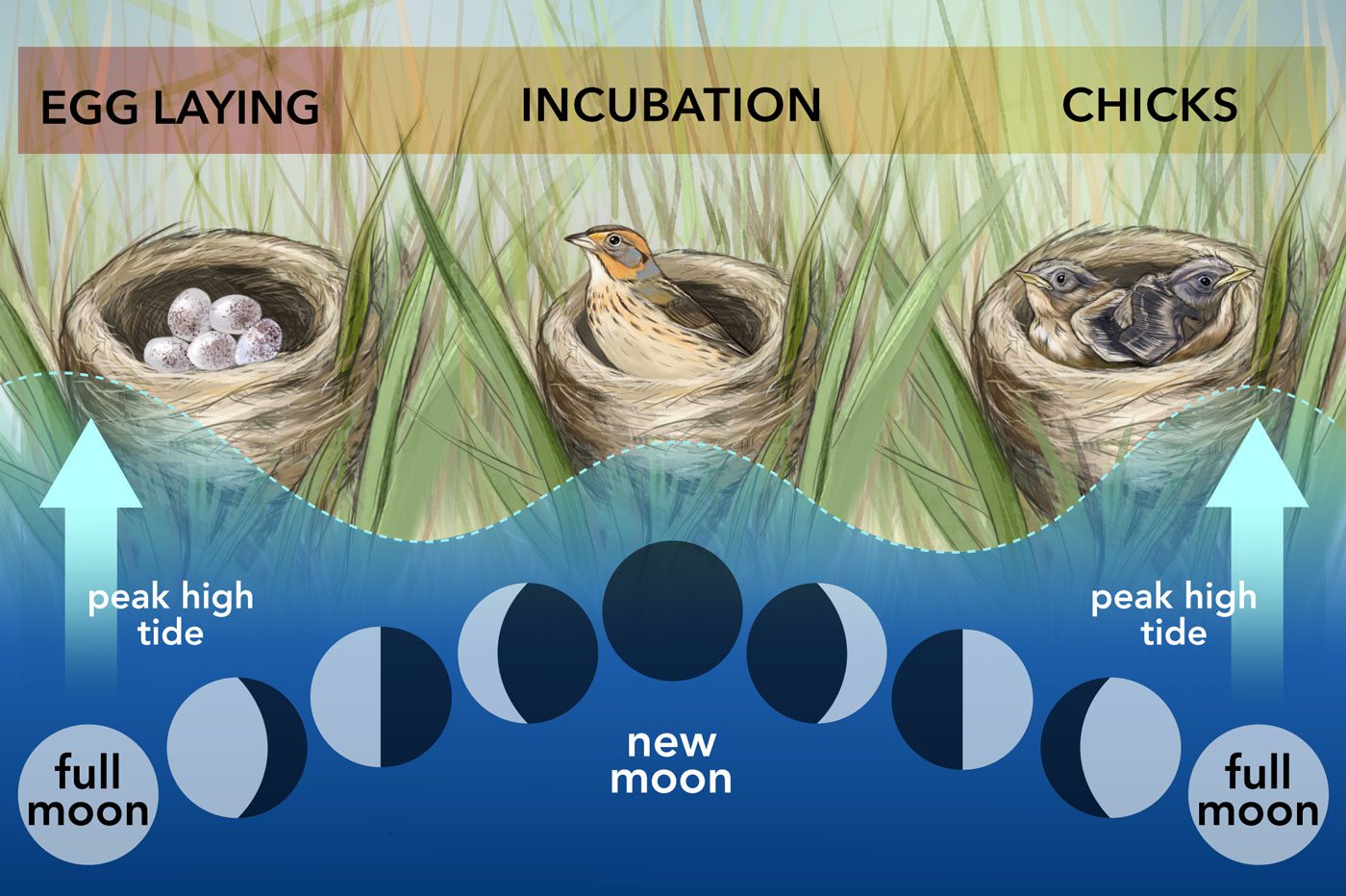

Saltmarsh Sparrows are especially vulnerable to sea-level rise because their reproduction depends on just that sliver of high marshes that only floods twice a month. Those high-tide peaks are normally spaced about 28 days apart, and Saltmarsh Sparrows have evolved a breeding cycle perfectly timed to fit within that schedule. They can mate, lay eggs, incubate, feed chicks, and fledge young off the nest in less than 26 days. Their nests are nestled in tufts of low-lying cordgrass vulnerable to flooding, so timing is critical to ensure chicks are strong enough to escape before the next high tide.

But as sea levels rise, so do tides, and now Saltmarsh Sparrow habitat is beginning to flood before the monthly peaks. Additional flooding from storms means nests are often drowned before chicks are reared.

Chris Elphick is a conservation biologist with the University of Connecticut who has extensively researched Saltmarsh Sparrows and their habitat needs. He is helping to lead a comprehensive survey of Saltmarsh Sparrow populations across their range that will take a few years yet to publish, but he says the data so far does not look promising.

Saltmarsh Sparrows nest among saltmeadow cordgrass in the higher areas of a tidal marsh. Females lay three to six eggs. Photo by Jonathan Fiely/Cornell Lab Conservation Media.

To succeed, the eggs must hatch and chicks fledge before the highest tides of the month. Photo by Jonathan Fiely/Cornell Lab Conservation Media.

Only 14% of the 143 nests he tracked in Connecticut in 2019 definitely fledged young—81%, or 115 nests, definitely did not. While it’s not always clear why nests fail, Elphick says, in cases where the reason was obvious, four out of five failures were due to flooding.

That trend likely played out up and down the coast last summer.

“If the sea level rises, it doesn’t just shut down one marsh, it affects the tides everywhere the birds live,” he explains. “It affects the entire population.”

The result, says Elphick: “You could cross this threshold point where suddenly every bird in the population is unable to reproduce. It could happen very quickly that they go extinct.”

To get more conservation attention for these birds, Shriver, Elphick, and other scientists formed the Saltmarsh Habitat and Avian Research Program and have been pressing the USFWS to designate the Saltmarsh Sparrow as an endangered species. A listing could bring more funding to state agency efforts to save marsh habitat.

Three years ago, the USFWS agreed to consider the question, but the service punted last spring, saying it wouldn’t make a decision until 2023. Shriver fears that could be too late.

“I don’t understand that logic,” Shriver says. “You don’t want to wait until the point when you have 200 birds left and are doing captive breeding.”

USFWS spokesperson Meagan Racey says the service is “committed to conserving Saltmarsh Sparrow populations,” but the agency needs more information about current and future conservation efforts for the Saltmarsh Sparrow before making a decision.

She also notes the agency has already spent $38 million at 14 locations since 2013 on Saltmarsh Sparrows, which has funded more than 180,000 acres of completed saltmarsh restoration projects thus far. And she points out that USFWS is an active participant in the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture’s efforts.

“We are aware of the conservation challenges impacting this species, which is why we are currently focusing our limited resources on establishing a comprehensive Saltmarsh Sparrow conservation program through the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture,” she says.

But saving the Saltmarsh Sparrow will be complicated.

Battling a Rising Tide

Birds have been brought back from the brink of extinction before. Conservation efforts famously resuscitated the California Condor from 21 condors left in the world to more than 300 condors flying free today. Even among Atlantic Coast shorebirds, the regional population of endangered Piping Plovers has more than doubled since 1986, thanks to efforts to protect their nests along sandy beaches from predators and human disturbance.

Battling rising tides, however, is an exponentially tougher challenge.

“If only it were predation, this would be so much easier,” Shriver laments. “But this is a hydrology thing, and a lot of these marshes can’t keep pace.”

To see what sea-level rise looks like today, look no further than Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on the Maryland coast. At first glance on a cloudy day, the open water perfectly reflects small islands of marshlands, stoic greens contrasting against the gray.

But the mirror of scattered wetlands used to be one contiguous marsh. Since the federal refuge was established in the 1930s, it has lost nearly half its wetlands—around 5,000 acres—to sea-level rise.

When water invades, the roots of high marsh plants decay and succumb, sloughing off into nothing. Here, critical Saltmarsh Sparrow habitat has been disappearing for decades.

“At first glimpse it doesn’t look bad, but this is breakup in process,” explains Matt Whitbeck, a USFWS biologist.

Sea-level rise is happening faster on the shore of Maryland than elsewhere along U.S. seacoasts because the land has also been slowly sinking since the end of the last ice age. What happens to the habitat here is a harbinger of what’s to come all along the Atlantic Coast.

But wetlands aren’t only being destroyed; they’re also being created. As saltwater moves inland, it kills hardwood trees like red maples and oaks, leaving so-called “ghost forests” of bedraggled-looking loblolly pines, some with green needles left on only half their tree limbs, interspersed between the bare trunks of trees that have already succumbed.

“They’re dead, but they don’t know it yet,” Whitbeck says.

Eventually the dead trees fall into the water, and the drowning woodlands become new wetlands. More than 3,000 acres of former upland forest has already been converted into saltmarsh at the Blackwater refuge.

This phenomenon is called marsh migration, and it could be the key to saving the Saltmarsh Sparrow. The Joint Venture’s conservation plan calls for enabling tidal marshes to migrate inland, stating this trade-off of woodlands for saltmarsh is “the single most important way we can offset or prevent the net loss of wetlands as sea levels rise.”

But as the experience at Blackwater has shown over the past 90 years, just letting nature take its course won’t necessarily be enough to help Saltmarsh Sparrows.

In addition to only nesting in high marsh, Saltmarsh Sparrows are picky about the kinds of plants they nest in, preferring low-lying cordgrass. The new marshes at Blackwater, however, are often dominated by the invasive phragmites plant, a reed that can grow up to 15 feet tall—and that Saltmarsh Sparrows avoid.

“It’s better than no wetlands at all. It provides some flood absorption and other functions,” Whitbeck explains. “But if you’re a Saltmarsh Sparrow, there’s nothing for you in this phragmites wetland, and that’s the real issue that we have.”

To offer the sparrows something different, Whitbeck started a pilot program on 15 acres of ghost forest where refuge staff have dedicated themselves to stopping the phragmites invasion, in hopes that native vegetation will have time to take hold. They’ve also proactively removed some snags of dead tree trunks, so Saltmarsh Sparrows won’t have to worry about any onlooking predators such as Northern Harriers in the pilot project area.

Much of the work was done prior to 2016. Saltmarsh Sparrows haven’t been seen breeding in the area to date, but Whitbeck says he didn’t expect results yet. He’s hopeful, and if successful, he says the strategy could be replicated fairly easily along the coast as ghost forests become more common.

“Sea-level rise isn’t all doom and gloom. Wetlands loss also equates to the creation of wetlands, if we plan it appropriately,” he says. “This landscape has the capacity for the creation of new marsh, it’s just trying to figure out where that’s going to happen, and if the marsh will provide habitat for these really critical species.”

Audubon Maryland–D.C. has also been experimenting with how to best enable marsh migration at the Chesapeake Audubon Society’s nearby Farm Creek Marsh property. There, the death of trees and their roots have caused weakened sediment, so when storms come, new marsh vegetation seemingly dissolves into open water.

“It can jeopardize our ability to rely on marsh migration progress, because these ponds appear to be permanent and they can get really big,” says David Curson, director of conservation at Audubon Maryland–DC.

Audubon is addressing the challenge by extending a nearby tidal creek in the hope that it will drain the ponded areas during low tides and give marsh grass a chance. So far, it seems to be working, Curson says, but only time will tell—and, as he points out, Saltmarsh Sparrows don’t have much to spare.

“We’re in a race against time to save this bird, and that…nags and keeps you awake because these techniques, a lot of them haven’t really been perfected,” he says.

How Many Sparrows Are Enough to Save the Species?

The joint venture has set what it hopes will be realistic expectations. In 2011, the total Saltmarsh Sparrow population was estimated at about 60,000 birds, but today it could be half that. The joint venture’s plan set a population objective of sustaining 25,000 Saltmarsh Sparrows over the long term.

That target is a best estimate (and a grim one at that) of what the population will fall to within the next few years. Weldon, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture coordinator, says the group knows they won’t be able to stop population declines before then, and that not all Saltmarsh Sparrow habitat can be saved. Instead, they hope that enough projects to restore and create new marshes will come online in time to hold sparrow populations steady within a few years.

The key is identifying where marshes will disappear next, and where they will possibly migrate to. That involves looking at land elevation and its slope, salt concentrations in water, and the general hydrology of an area to predict where marsh migration will occur.

And, it will require people.

“We need more people to be protecting those areas, so the land is there for the [saltmarsh] migration and it doesn’t get built upon,” Weldon says.

Chris Field is a postdoctoral fellow at the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, a partnership between the National Science Foundation and the University of Maryland to study how humans interact with nature. Field studies ways to conserve tidal wetlands in the face of climate change, and he notes that enabling marsh migration will require the buy-in and participation of the people who currently own upland areas near the coast—the uplands that are identified as ripe for conservation to allow marsh migration.

But, Field says, making that happen will be challenging: “I think the situation is pretty dire.”

Currently Saltmarsh Sparrows are getting squeezed between growing human communities and rising tides. Coastal cities and towns are paving or building directly on marshes, destroying habitat. Other development close to wetlands, even if it doesn’t touch the saltmarshes, can have indirect impacts such as increasing stormwater runoff and pollution, which can change marsh plant communities and make them unattractive for nesting Saltmarsh Sparrows. Human development already covers more than 40% of coastal land between Massachusetts and Florida. Another 60% of what’s left is expected to be developed in the future, according to the projections in the Joint Venture’s plan.

Rob Young, who directs the Study of Developed Shorelines program at Western Carolina University, blames development more than sea-level rise for the Saltmarsh Sparrow’s predicament. Young says that marsh migration is a natural response to shifting seas and notes that coastlines have always moved due to storms and other factors. But now, he says, development is interrupting this process: “The real conflict that we have is the fact that we are trying to create this… human infrastructure on [top of coastal marsh] systems that have always been dynamic and really need to be dynamic in order to survive.”

Incentives like federally backed flood insurance and emergency aid to rebuild after hurricanes have encouraged and increased development in coastal areas, exacerbating the problem, Young says.

But another federal program, conversely, removes incentives for coastal development; it’s called the Coastal Barrier Resources Act. When President Ronald Reagan signed it into law in 1982, he said the legislation “will save American taxpayers millions of dollars while taking a major step forward in the conservation of our magnificent coastal resources.”

The act doesn’t prohibit development in risky areas, but designates relatively undeveloped coastal areas as “units” in which no federal funding or assistance can be used. In 1982, the system included 590,000 acres in which federal funds can’t be used on things like road construction, flood insurance, and dredging. Communities expanding into those areas are held fiscally responsible for the risks and costs of living on the coast.

So far, it’s worked. Between 1983 and 2010 the act saved more than $1.3 billion in federal funds, according to estimates of disaster recovery costs. What’s more, a 2007 report from the Government Accountability Office found that 84% of units within the program remained totally undeveloped, while only 3% experienced “significant development” with 100 or more new structures.

USFWS is currently working to modernize maps of areas included under the Coastal Barrier Resources Act. The update, which began in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, has the potential to add 130,000 acres to the program, though the changes will have to be approved by Congress.

Lawmakers in the House also recently introduced a bill aimed at protecting coastal ecosystems, including tidal and saltmarshes that help prevent climate change by storing carbon. The Blue Carbon for Our Planet Act has bipartisan support in the lower chamber, with bill sponsors saying they hope to simultaneously protect coastal habitats and mitigate climate change. But, it remains to be seen whether the Senate will support the legislation.

Saltmarshes Are Good for People, Too

In the meantime, many coastal communities are starting to acknowledge that conserving coastal habitat can benefit humans, too. The concept of so-called “green infrastructure”—using wetlands or sand dunes instead of concrete sea walls to help combat storm surge and flooding from hurricanes—is catching on.

Research from Rachel Gittman, a professor of coastal policy and conservation biology at Eastern Carolina University, shows that, in many cases, using natural systems makes more fiscal sense than building sea walls.

“We found that if a property owner has a natural marsh, they are spending fewer dollars on maintenance of their shoreline, they are spending fewer dollars in terms of damage repairs [from sea surges and storms], and they’re also experiencing damage less frequently than their counterparts who have bulkheads,” she says.

Awareness about the importance of these “living shorelines” has grown since Superstorm Sandy devastated many areas of New York and New Jersey in 2012. Sandy caused $37 billion in property damage in New Jersey alone. But in the beach village of Cape May Point, flood insurance claims after Sandy were half of previous comparable storms—in part because nearby wetlands on The Nature Conservancy’s South Cape May Meadows Preserve acted as a catch basin for floodwaters. The Conservancy says that the preserve could save taxpayers nearly $10 million in avoided flooding and damage costs over the next 50 years.

Numbers like that have attracted the attention of the lawmakers in Congress tasked with approving and funding federal flood control projects. Many on both sides of the political aisle now acknowledge that “green infrastructure” is key to building communities that are resilient to climate change and sea-level rise.

But not all green infrastructure creates excellent wildlife habitat. In New Jersey, for example, a green-infrastructure effort to make the Meadowlands waterfront area more resilient to climate change includes installing permeable pavement, bioretention basins, and human-made wetlands. That kind of green infrastucture doesn’t have much, if any, high-marsh habitat value for Saltmarsh Sparrows.

According to Young, the developed shorelines researcher at Western Carolina University, marsh migration is “a gagillion times better” than human-made green-infrastructure substitutes to help species at risk of climate change.

Sea-level rise, Young says, will eventually swamp the small strips of natural wetlands that are left between communities and the sea. In New York and New Jersey, where coastal development is only accelerating, Young says: “The habitat is doomed.

“At some point in the future, they are just going to be gone, and we’re going to have water bumping up against our urban infrastructure.”

The Cadillac of Restoration Projects

The joint venture’s saltmarsh plan spotlights facilitated marsh migration as a “key implementation action,” but there are other complementary conservation strategies in the plan, too—such as elevating existing saltmarshes by spraying thin layers of sediment onto them. The hope is that raising the elevation of those areas by just 10 to 12 centimeters will get them above the immediate danger of sea-level rise, allowing cordgrass to repopulate and create good Saltmarsh Sparrow habitat.

One such example of saltmarsh elevation was a pilot project by USFWS biologist Matt Whitbeck at Maryland’s Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. It was completed on 30 acres in 2016 and has already seen the return of American Black Duck and Black Rail. But so far, no Saltmarsh Sparrows.

Whitbeck says he estimates it could take nearly seven years for the “plant dynamics to shift” in such a way that encourages Saltmarsh Sparrows. But the reappearance of other saltmarsh birds is “promising,” he says.

“It’s an indication of the boost in elevation, that the wildlife is responding to it.”

Yet another strategy involves restoring natural water flows to coastal wetlands that have been ditched, drained, and engineered for other purposes over the past century. The Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware provides a gargantuan example.

There, natural saltmarshes were converted into freshwater wetlands decades ago, and, until recently, the USFWS managed the area to support waterfowl, making it a popular duck hunting spot.

But the freshwater ponds were destroyed over the years by a series of storms that blew a hole in the sand dunes that separated freshwater from the sea. The resulting breaches ruined the wetlands and flooded out roads and nearby agricultural fields.

A subsequent $38 million federal project at the refuge sought to return the area to its natural state, restoring two miles of sand dunes and 4,000 acres of tidal marsh—the biggest effort of its kind on the East Coast.

“This was really a hydrology exercise, trying to redo the plumbing of the place,” Prime Hook refuge manager Al Rizzo says.

By removing human-made floodgates, the natural tidal water flows were restored, which should bring more sediment into the system and eventually serve as the foundation for more marsh plants. The work was completed in 2016, but there are still large areas of open water in the restoration area.

“This year was a pretty nice jump in terms of footprint, but how long it takes before everywhere is recovered is anyone’s guess,” Rizzo says. “But the objective was to get the water right. If we could get the hydrology right, then we felt that the vegetation could adapt.”

It could take up to eight years—a timeline Rizzo and his staff acknowledge may be too slow for the Saltmarsh Sparrow.

“I personally am impatient, I wish we were lousy with [Saltmarsh Sparrows],” Rizzo says. “But when I drive around and I look and I see places that I know were underwater three years ago that are now vegetated, it seems to be working. And it seems to be working at a pace we anticipated.”

In other words, Rizzo built it, and now he’s waiting to see if the Saltmarsh Sparrows will come.

Many at USFWS believe the Prime Hook saltmarsh restoration will ultimately help Saltmarsh Sparrows. But the project is too massive and too costly to be widely replicable across the sparrow’s range, says Weldon, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture coordinator. While she too acknowledges the good work being done at Prime Hook, she calls it “the Cadillac of restoration projects.”

“Most of us don’t have $38 million to do a coastal restoration project,” she says.

A bit farther north, the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge in Newburyport, Massachusetts, is piloting other promising new saltmarsh conservation strategies that could more easily translate to other areas.

The Parker River refuge is pockmarked with ditches installed during various attempts at mosquito control dating back to the 1700s, says Nancy Pau, a USFWS wildlife biologist there. Today, sediment and debris have clogged many of the ditches, pooling water and drowning marsh grasses.

Pau says the refuge is using two strategies to solve the problem: “unplugging” some of the ditches to allow water to drain, and then “healing” the ditches by filling them with hay in an attempt to trap sediment and coax natural vegetation growth.

Despite the ditches, the marshes at Parker River are actually healthy, unlike those at Blackwater or Prime Hook. Pau’s effort is a preemptive action to expand habitat on a small budget before sea-level rise becomes a problem.

“We have a healthy marsh, so we aren’t really restoring, we are just helping the system maintain its function,” she says.

Weldon says the strategies being deployed at Parker River, and Prime Hook, and Blackwater will all be needed to save the Saltmarsh Sparrow.

“There is not a lot of time to figure it out, so we are all hands on deck,” she says. “We think we can do it if enough people get on this bus and do this kind of work.”

With so much effort, time, and money required to try to save a small, brown bird, some might wonder whether it’s all worth it.

“You could take the idea that they are an evolutionary dead end, so who cares?” ponders Elphick, the University of Connecticut conservation biologist. “But that’s what makes the natural world so interesting, is that you have all of these weird species and behaviors.”

Weldon agrees. And, she notes, Saltmarsh Sparrows aren’t the only birds threatened by climate change. They’re just the first.

“The way I see it, we can throw everything we’ve got at this bird and hopefully we’ll be successful and prevent further population decline,” Weldon says. Then she takes the glass-half-empty approach: “But let’s say we’re not, and we lose the Saltmarsh Sparrow. By the time that happens, hopefully we’ll know what to do…and be able to save the saltmarsh and the other birds there experiencing declines.”

What’s more, it’s not just about the birds. Human efforts to conserve or preserve wetlands will almost certainly benefit human coastal communities as seas invade.

In other words, by working to save Saltmarsh Sparrows, we could be saving ourselves.

“A healthy bird population means a healthy marsh, and a healthy marsh creates healthy human communities,” Weldon says. “It’s all connected.”

Ariel Wittenberg is the water reporter for E&ENews, an energy and environment news service based in Washington, D.C. Previously, Wittenberg worked for The Standard-Times in New Bedford, Mass., covering the offshore wind industry and toxic waste.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library