Saving the Wood Thrush: Q&A With Ron Rohrbaugh

By Pat Leonard

From the Autumn 2014 issue of Living Bird magazine.

October 15, 2014

Related Stories

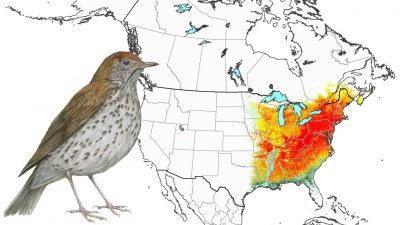

Our woodlands would seem terribly empty without the flutelike song of the Wood Thrush echoing through the trees. And yet the overall population of this enchanting forest songbird of the eastern United States and southeastern Canada has dropped by more than half in the past 50 years. The newly formed International Wood Thrush Conservation Alliance (IWOTHCA) aims to find out why and to try to reverse this trend before the bird’s situation becomes too dire for conservation measures to work. The Cornell Lab’s Ron Rohrbaugh is chair of the group.

What is the International Wood Thrush Conservation Alliance?

The group is a consortium of biologists from academic institutions, agencies, and non-profit organizations, who are focused on studying and conserving Wood Thrush populations and raising awareness about the conservation needs of associated forest birds and their habitats. Our mission is to ensure the long-term viability of Wood Thrush populations and their habitats through science-based, full-life-cycle conservation planning, management, and education.

Why are Wood Thrushes declining?

Habitat loss on the breeding and wintering grounds is the biggest problem. The habitats become degraded through forest fragmentation, overbrowsing by deer, invasive plants, and the effects of acid rain. When forest health is compromised, a whole cascade of problems, such as increased nest predation and cowbird parasitism, arise. We need to find out what stressors are impacting habitat quality and how that reduction in quality impairs a Wood Thrush’s ability to breed successfully.

What is full-life-cycle conservation?

Traditional conservation strategies for migratory birds mostly rely on protecting and creating breeding habitat. Although this can increase breeding populations, research has shown that songbird populations are most sensitive to the mortality of adults and young, which is often highest during migration. Full-life-cycle conservation strategies could help resolve this disconnect by pinpointing the locations and times when management actions would be most effective. IWOTHCA includes researchers from York University in Canada and the Smithsonian Institution, who are tracking migratory Wood Thrushes with geolocators and developing quantitative full-life-cycle models to reveal when populations are being limited.

How is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology contributing to the research?

Two important Cornell Lab citizen science datasets can help us understand what’s happening with the Wood Thrush. Although the bird’s numbers have been dropping since the 1970s, they are still often seen by birders and reported to eBird. We intend to use eBird data to help track migration and to map stopover sites and the winter range of the species in Latin America, where deforestation is a major issue. Birds in Forested Landscapes, which ran from the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s, holds a treasure trove of breeding data on the Wood Thrush. We plan to analyze these data, along with data from other sources, such as the Breeding Bird Survey, to help determine how changes in forest structure might be impacting Wood Thrush reproduction.

Why are Wood Thrushes so vulnerable to cowbird nest parasitism?

Brown-headed Cowbirds were originally concentrated primarily in the Great Plains, where they followed the vast herds of bison. Bird species that evolved side by side with them learned to deal with cowbird eggs that were laid in their nests. But the clearing of eastern forests for farming and development allowed cowbirds to expand eastward and to take advantage of “naïve” host species, such as the Wood Thrush, that never learned how to recognize and get rid of cowbird eggs.

Is there a broader benefit to what IWOTHCA is trying to do?

Because Wood Thrushes are forest specialists, many other bird species that rely on large contiguous tracts of healthy forest habitat will benefit from the conservation of this species. Some of the most important include Louisiana Waterthrush, Swainson’s Warbler, and Acadian Flycatcher. It’s important to keep in mind that forested landscapes are not static. Each bird species has its own niche and relies on forest of a certain age. In our conservation efforts, we’ll strive to create a shifting mosaic of forest patches that vary in age and size. This provides the greatest benefit to the highest number of forest birds. Protecting Wood Thrush habitat in Mexico and Central America will benefit dozens of tropical species, such as the endangered Great Green Macaw.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library