Put a Cork in It: Conservation in Your Wine Bottle

By Hugh Powell; Photograph by FLPA/John Hawkins/Minden Pictures

January 15, 2012

Here’s an exercise in conservation biology you can try at home: Open up a nice bottle of wine, pour yourself a glass, and have a look at the stopper. Chances are you’re holding a cork: a piece of history; a miracle of evolution; and a key to the conservation of thousands of European birds.

Or you could be holding a slug of plastic or a screw cap, two newish approaches to keeping wine in a bottle. They safeguard your wine against the musty-tasting contaminant trichloroanisole, which can develop in corks. And they cost about one-sixth as much as a cork.

In a world awash in cheap, decent wine, shaving prices makes for good business. Some 70 percent of Australian wines now use screw caps, and “alternative closures” are gaining popularity in the United States as well, especially among white wines, which don’t need to age. In response, cork prices have fallen by about 30 percent since 2003, according to Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

The new closures are undercutting cork farming, a centuries-old profession in the Mediterranean and a star example of a sustainable industry. Ecologists have taken notice, because cork forests are havens of biodiversity. Covering much of the southern Iberian Peninsula, they are one of the last refuges of the Iberian lynx. They provide habitat for Spanish Eagles and Black Storks. Hundreds of thousands of migrants stop over in cork oak landscapes, including an estimated 70,000 Common Cranes and 6 million Common Wood-Pigeons.

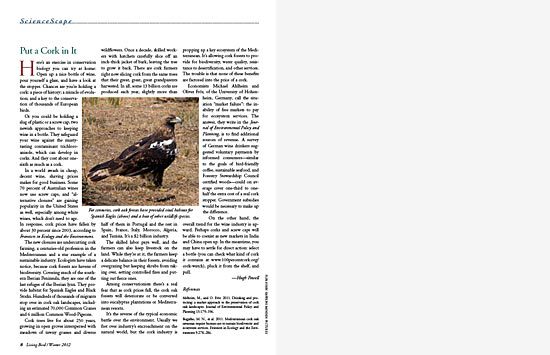

Cork trees live for about 250 years, growing in open groves interspersed with meadows of tawny grasses and diverse wildflowers. Once a decade, skilled workers with hatchets carefully slice off an inch-thick jacket of bark, leaving the tree to grow it back. There are cork farmers right now slicing cork from the same trees that their great, great, great grandparents harvested. In all, some 13 billion corks are produced each year, slightly more than half of them in Portugal and the rest in Spain, France, Italy, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It’s a $2 billion industry.

The skilled labor pays well, and the farmers can also keep livestock on the land. While they’re at it, the farmers keep a delicate balance in their forests, avoiding overgrazing but keeping shrubs from taking over, setting controlled fires and putting out fierce ones.

Among conservationists there’s a real fear that as cork prices fall, the cork oak forests will deteriorate or be converted into eucalyptus plantations or Mediterranean resorts.

It’s the reverse of the typical economic battle over the environment. Usually we fret over industry’s encroachment on the natural world, but the cork industry is propping up a key ecosystem of the Mediterranean. It’s allowing cork forests to provide for biodiversity, water quality, resistance to desertification, and other services. The trouble is that none of these benefits are factored into the price of a cork.

Economists Michael Ahlheim and Oliver Frör, of the University of Hohenheim, Germany, call the situation “market failure”: the inability of free markets to pay for ecosystem services. The answer, they write in the Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, is to find additional sources of revenue. A survey of German wine drinkers suggested voluntary payments by informed consumers—similar to the goals of bird-friendly coffee, sustainable seafood, and Forestry Stewardship Council certified woods—could on average cover one-third to one-half the extra cost of a real cork stopper. Government subsidies would be necessary to make up the difference.

On the other hand, the overall trend for the wine industry is upward. Perhaps corks and screw caps will be able to coexist as new markets in India and China open up. In the meantime, you may have to settle for direct action: select a bottle (you can check what kind of cork it contains at www.100percentcork.org/cork-watch), pluck it from the shelf, and pull.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library