People Power and Sustainable Forestry Keep Deforestation at Bay in Guatemala

By Hugh Powell

Magnolia Warbler in Mexico. Photo by Edgar Miceli via Birdshare. October 11, 2016From the Autumn 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

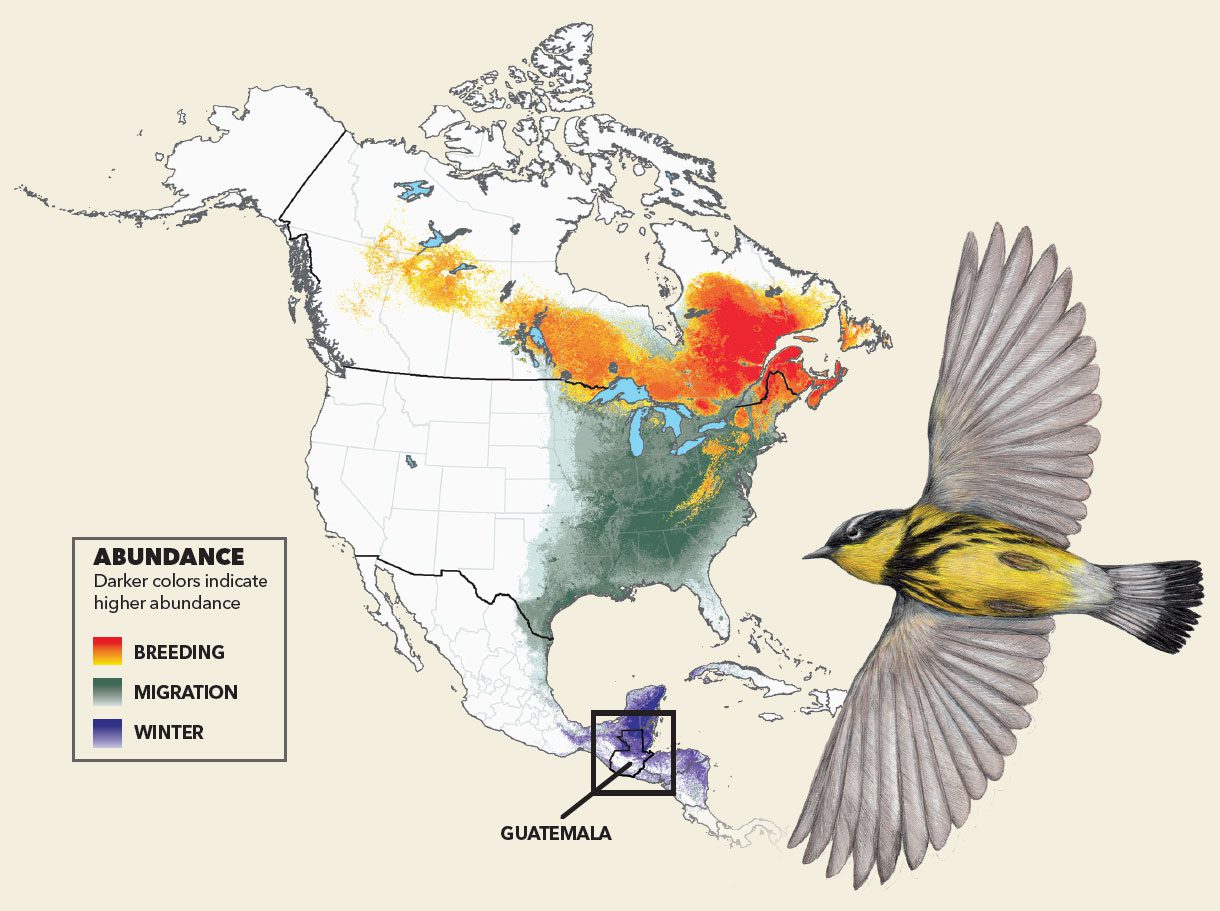

Quick question: Where’s the best place in the world to find a Magnolia Warbler? Is it the great boreal forest of Canada, where an estimated 38 million of these gorgeous songbirds breed? Or perhaps it’s someplace like Cape May, New Jersey, in the third week of May, just after a cold front has passed through.

As it turns out, the correct answer is the Yucatán Peninsula, where Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize come together. There, most of the world’s Magnolia Warblers cram into winter grounds just one-quarter the size of their breeding range. At times, nearly every foraging flock flickers with the white-black tail pattern of a Magnolia Warbler or two, shepherding the group along as if they were chickadees.

Magnolia Warblers aren’t the only migrants there. The Yucatán is a key wintering ground and a major migration crossroads for 60 species of Neotropical migrants, including Ovenbird, Kentucky Warbler, Indigo Bunting, and Orchard Oriole.

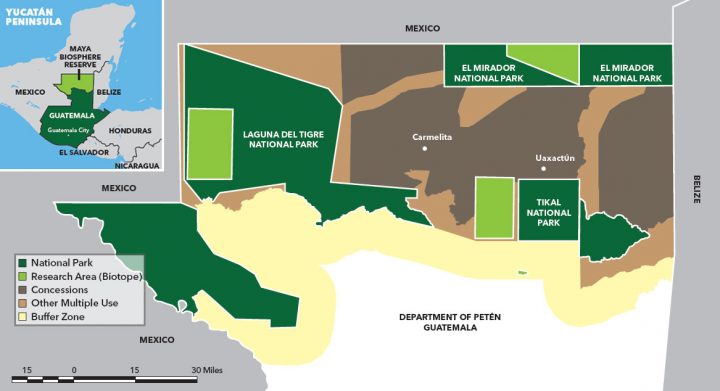

But the Yucatán, like most of tropical America, is under intense development pressure. Deforestation is rampant, and logging, oil extraction, agriculture, and narcotraffickers are gnawing at the edges of whatever forest chunks are left. The biggest chunk of all is the Maya Biosphere Reserve of Guatemala, a vast, 8,100-square-mile mixed reserve of legally protected national parks and “multiple use zones” that allow limited development.

In 1997, that patchwork of land reserves became a proving ground for a different kind of conservation model, one that grants local villagers the go-ahead to make a living from the land, instead of walling it off as a national park. The Guatemalan government awarded local communities both the right and responsibility to manage tracts of forest that became known as “concessions.” The rules allowed the locals to profit from the forest but required them to document good stewardship.

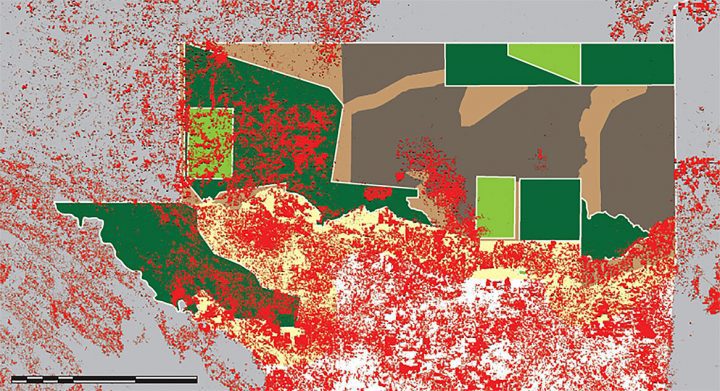

Over the following 14 years, according to a 2015 Rainforest Alliance report, the experiment worked beyond anyone’s expectations: while deforestation crept into some of the national parks within the reserve, losing forest at almost double Guatemala’s national average, most of the concessions managed by local communities lost essentially no forest.

The local people have filled an important gap in safeguarding many parts of the Maya reserve, says Claudia Burgos, a research associate at the Center for Conservation Studies (known as CECON) and a professor at Guatemala’s University of San Carlos.

“It’s important that the local people get involved in this way,” she said. “There are not too many park rangers in these areas, and they don’t [make] regular visits.” With the locals living and working in the protected areas, they’re perfectly positioned to fill the gap in monitoring and protection.

CECON has a place on the Maya Biosphere Reserve’s advisory board, along with Guatemalan agencies and international groups including the Wildlife Conservation Society and Rainforest Alliance. Burgos hopes that with the training CECON provides in natural history, monitoring techniques, and data analysis, the locals can benefit even more from their concessions and diversify their economic prospects by catering to ecotourists.

The Maya Biosphere Reserve consists of a patchwork of national parks (dark green), research areas (light green), and privately managed concessions (brown). Maya Biosphere Reserve map from WCS-CEMEC.

Red areas indicate forest loss since 2000, including severe losses in Laguna del Tigre National Park and very little loss in the concessions. Deforestation data from Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA.

Think of the Maya reserve as the glittering emerald heart of the Yucatán: a horizon-to-horizon forest that spans almost a fifth of Guatemala’s land area. Here, jaguars still hunt tapirs, and the forest rings with the gravel-throated din of howler monkeys. Great Curassows and Crested Guans—typically the first birds to disappear when people arrive—strut along muddy trails or screech from the tops of mahogany trees. This is where Tikal’s famous pyramids lie, although Tikal National Park itself takes up just 3 percent of this vast preserve.

To the north, against the Mexican border, lies El Mirador National Park, an expanse of Mayan ruins even older, larger, and more remote than Tikal, currently accessible only via a two-day, mule-assisted hike or, for the well-off, a helicopter ride. At the reserve’s western edge lies Laguna del Tigre, a very different national park. In the 1980s, a road was paved through Laguna del Tigre for oil exploration, providing a conduit for deforestation. Despite the land’s protected status on paper, it lost 30 percent of its forest between 1997 and 2013 (watch a 28-year time-lapse of forest loss via satellite imagery). Over the same period concessions managed by the tiny towns of Carmelita and Uaxactún lost less than 1 percent of their forest.

Reserves like Laguna del Tigre highlight the steep odds that parks in the tropics are up against. Though they’re legally protected, they often lack the funding necessary to enforce that protection on the ground.

Roads can make things worse, attracting people who illegally clear land—as happened after the oil road went in at Laguna del Tigre. And it creates a continuing problem, because the new arrivals have no prior relationship with the land and no legal obligation or incentive to maintain the forest.

Fortunately, Laguna del Tigre makes up only 14 percent of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, along with five other parks, four research preserves, and 14 concessions. This patchwork of land types, along with the reserve’s sheer size and remoteness, have helped it to remain the crown jewel of protected forest in the Yucatán.

The actions of local communities have been part of that success, says Benjamin Hodgdon, director of forestry at the Rainforest Alliance and author of the 2015 report.

“The evidence is stark and it’s absolutely clear,” Hodgdon says. “When you hand over rights to local communities and give them incentives to manage the forest, and when you provide them with support to do it sustainably,” deforestation can be held in check.

The villages of Carmelita and Uaxactún were founded more than a century ago by chicleros who tapped the local sapodilla trees to make chewing gum for export to companies such as Wrigley. Today, selective logging of mahogany and a few other tree species is a $13 million business and provides much of the communities’ income. Families also earn money from harvesting a palm frond known as xate (pronounced “shah-tay”). The leaves are popular in the U.S. and Europe for floral arrangements, and annual harvests in the Maya reserve are worth $5.7 million, according to the Guatemalan government. Rounding out the balance sheet are chicle, allspice berries, and ecotourism associated with Tikal and El Mirador.

A farsighted feature of the Guatemalan plan was the stipulation that all forestry operations—formally known as concessions—must earn Forest Stewardship Council certification within 3 years and maintain it through annual and five-year audits. Despite the $13 million that tree harvests bring in, logging intensities in the reserve are among the lowest recorded in tropical lowlands. And the area’s xate harvesters are among the few sources of FSC-certified palm leaves, in stark contrast to severe overharvesting elsewhere in Central America.

In the last 15 years, while 10 concessions have thrived, four have been revoked or suspended for not meeting requirements, losing their legal permission to harvest from the forest. The move gives concession management the kind of teeth that are missing from parks that suffer from illegal activity, like Laguna del Tigre.

When community management works, it’s because the locals have a deep commitment to the land they live on, says Viviana Ruiz-Gutierrez, a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

“There’s a very common misconception that if we don’t do something—we as foreigners—then it’s all going to go down the drain,” says Ruiz-Gutierrez, a native Costa Rican who spent her high school years in Massachusetts. “But it’s not because [locals] don’t want to,” she said, “It’s just their capacity is limited and their funds are limited.”

This fall, Ruiz-Gutierrez plans to work with Burgos and others at CECON to build up that capacity. Recognizing that locals are the best people to monitor their forests, the team plans to equip them with binoculars and cameras and help them manage their data using eBird.

The work they’re already doing to satisfy certification requirements amounts to citizen science, Ruiz-Gutierrez says. “They are the ones who are out measuring their trees, counting birds, doing things because they have to to keep their lands, and to get better prices for their products.” With training in data handling, they’ll also be gaining technological knowledge that will help them run their businesses.

For North American birders, it’s a happy coincidence that the forest these communities are protecting is also a vital refuge for Neotropical migrants (not to mention more than 300 tropical year-round resident bird species). According to eBird occurrence models, 22 migratory eastern songbirds spend 45 percent of their year in the Yucatán, all clustered into an area one-third the size of their summer ranges.

That’s why the remaining forest in and around the Maya Biosphere Reserve is so important. Compared to the North American breeding grounds, the Yucatán harbors more birds per acre and for longer—almost half the year. Conserving forest there is almost like donating to public radio during a three-for-one matching gift offer.

Despite the encouraging success of concessions in the Maya reserve, the problem of how best to stave off deforestation has not been put to rest yet.“Community-owned reserves can certainly be good, because there’s impetus and incentive to manage the area,” says Alexander Lees, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab and expert on South American forest conservation. “People have an interest in not being the last person in there removing the last tree.”

But even the best-managed concessions aren’t as good as untouched forest, he argues. In a recent study in Brazil, Lees helped document the degradation that can happen to rainforest even when it is not deforested outright. The study recorded losses in bird, plant, and dung-beetle diversity in the state of Pará in partially harvested or burned forests that were on par with losing 40,000 square miles of forest. “I think it’s slightly unfair to say that the parks aren’t working,” Lees says. “The parks aren’t working because they’re not being funded.”

For a prime example of what happens when parks are funded, look no farther than Tikal. Despite hosting 160,000 tourists per year, Tikal—“a fantastic, amazing, jaw-dropping place,” Hodgdon says—saw virtually zero deforestation in the Rainforest Alliance’s study.

Why was it spared? Because those tourists were paying $20 entry fees, providing the funding for protection. It works for a world-renowned park with a steady flow of tourists, Hodgdon says, “but that’s not viable for a 2.1-million-hectare area” like the rest of the Maya reserve.

But if parks are expensive to maintain, sustainable forest concessions are expensive to set up. Forest Stewardship Council audits run thousands of dollars, often putting them out of the financial grasp of small communities. Since 2000, the U.S. Agency for International Development and other organizations have spent tens of millions of dollars to help the Maya reserve concessions pay certification costs and invest in equipment.

Now, more than a decade later, several concessions own their own sawmills and workshops, have worked certification into their business models, and are profitable. In the Maya reserve, smaller communities are profiting from their deep knowledge of the land, both through forest management and by guiding ecotourists on routes like that two-day trek into El Mirador. And that’s where there’s room for economic growth: El Mirador gets less than 1 percent of Tikal’s tourist traffic—around 1,500 hardy visitors per year.

CECON and the Wildlife Conservation Society are helping locals prepare for ecotourism. CECON has run environmental education workshops in a half-dozen communities adjacent to the reserve’s research preserves, and has tapped community members to help study the rare Baird’s tapir. Over the past two years, the Wildlife Conservation Society has trained 64 bird guides, earning government certification as ecotourism guides.

If these efforts work, and ecotourism grows in the region, it will be a needed boost to the income provided by forestry. Despite the success of selective harvesting and xate gathering, the work employs just a few thousand of the region’s more than 100,000 inhabitants. As many as 80 percent of the people have no regular jobs, according to a Guatemalan government report.

Travel-hungry birders can do their part simply by hiring guides.

“So many people come to [the reserve] to do bird watching, but they go to Tikal,” Burgos says. The birding is just as good—perhaps better—in more remote areas such as El Mirador. For foreign visitors, “taking these kinds of tours that visit the [smaller] communities, taking local guides, I think it’s very helpful,” Burgos says. “It’s another way to [add] to their economy.”

According to Ruiz-Gutierrez, that delicate balance between forest conservation and economic output is the key to keeping much of the Maya Biosphere Reserve intact.

“Because if no one makes money, those forests go away,” she says. “That’s the bottom line.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library