Many Conservation Plans Have a Sex Bias, Study Finds

By Pat Leonard

January 9, 2020

From the Winter 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

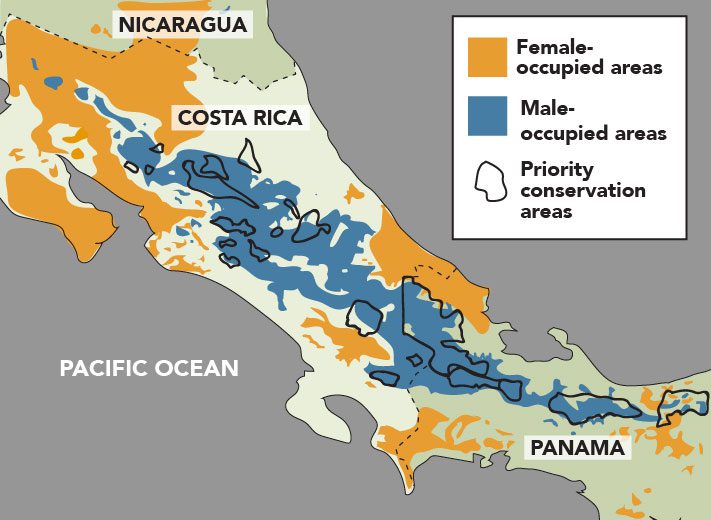

When Golden-winged Warblers migrate south to Central and South America for the winter, the males and the females go their separate ways—with the males in the higher elevations and females in the lower elevations.

But scientists conducting bird surveys in these tropical areas don’t typically account for this kind of sexual segregation among migratory birds on the nonbreeding grounds, says new research published in the journal Biological Conservation. As a result, the female birds are often left out of conservation planning.

“When conservation plans don’t explicitly address the habitat requirements of both sexes, there’s no guarantee both sexes will be protected,” said lead author Ruth Bennett, who conducted the research while earning her PhD at Cornell University and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. “Overlooking female-dominated habitats can lead to unforeseen population loss, which is especially critical for species of conservation concern.”

As a case study for this research, Bennett and her coauthors studied Golden-winged Warblers, a fast-declining songbird that is suffering from deforestation on its nonbreeding grounds. The scientists found that since the year 2000, female golden-wings had lost twice as much habitat as their male counterparts. Despite the high threats faced by females, the researchers found that previous conservation planning efforts had disproportionately prioritized male-dominated habitats.

“Our research is an important reminder that ‘one-size-fits-all’ conservation does not accommodate the needs of both male and female birds any more than a one-size-fits-all approach would work in meeting the needs of men and women at work and at home,” says study coauthor Amanda Rodewald, codirector of Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

The researchers reviewed conservation plans for 66 declining migratory bird species and found that sexual segregation in nonbreeding areas is common. However, only three plans even mentioned sexual segregation (the plans for Bicknell’s Thrush and Black-capped Vireo, and now for Golden-winged Warbler—thanks to the contribution of research findings by Bennett).

While Bennett and Rodewald acknowledge that surveying for females among these migratory bird species can require more searching (they’re less colorful and less vocal; see The Forgotten Female: How a Generation of Women Scientists Changed Our View of Evolution,” Summer 2019), the extra effort will probably be worth it.

“It could allow us to be much more strategic and save money,” says Rodewald. “Conservation plans are stronger, and more likely to be effective, when they explicitly consider the needs of females.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library