Gene Differences May Help Golden-winged Warblers Get to Their Wintering Grounds

By Marc Devokaitis

March 31, 2020

From the Spring 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Young-of-the-year warblers don’t have much time to learn how to migrate.

Juveniles of Neotropical migratory bird species are often just weeks out of the nest when they face the challenge of flying thousands of miles south— through the dead of night and possibly stormy conditions—to a place in Central or South America where they’ve never been before.

Because of the astounding, seemingly innate ability of birds to navigate across the hemisphere, scientists have long speculated that seasonal long-distance migration is wired into migratory birds—somehow part of their DNA. But, scientists have had a difficult time narrowing in on the specific genes that might guide migration.

A study published last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences changes that. The researchers narrowed in on a single gene in Golden-winged Warblers that seems to be associated with migration strategy.

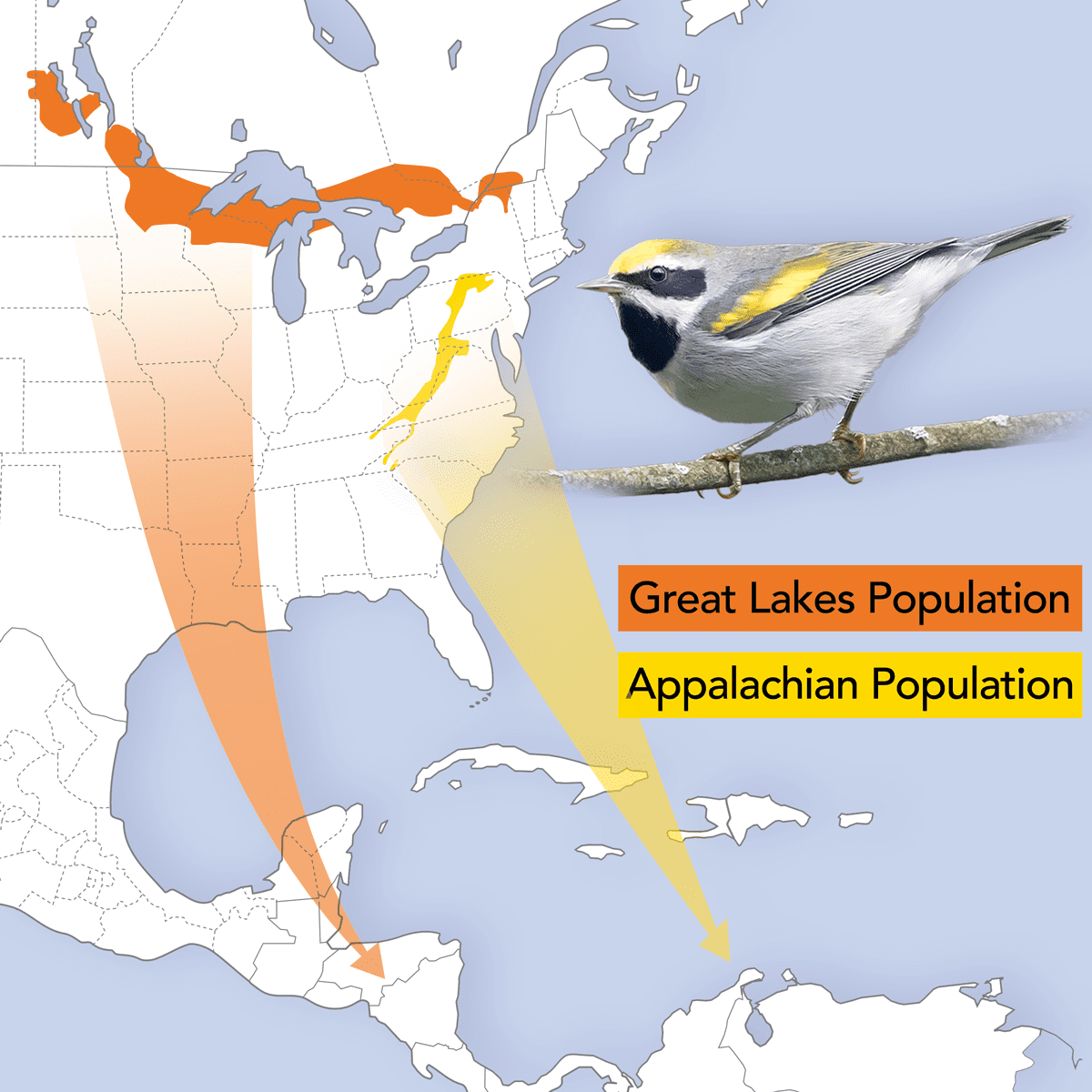

Golden-winged Warblers that breed in Appalachia and the Northeast tend to migrate to South America—a much longer journey than the golden-wings that breed in the Midwest—and usually winter in Mexico and Central America. By analyzing blood samples from a previous study that tracked migration patterns of birds, the research team uncovered a region within the Z chromosome that differed significantly in birds that wintered in South America, as compared to the ones that wintered in Central America. And within that region, there was only a single gene called VPS13A; its function hasn’t been previously studied in birds.

“This is very speculative at this point, but we think it could be involved in clearing reactive oxygen [molecules]… that can build up during a prolonged migration and damage cells,” said David Toews, lead author of the research, in a press release. Toews is a biology professor at Penn State University, and he conducted much of this research when he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology from 2014 to 2018.

“We would like to perform additional studies to know when and in what tissues this gene is expressed in these birds,” said Toews.

Golden-winged Warblers are facing steep population declines, particularly in the Appalachian portion of their range. Toews believes this research into the intersection between migration and genetics provides a potential avenue of hope. He says the research “speaks to the strong connectivity between wintering and breeding areas, and how genetically similar Golden-winged Warbler populations are [across their range].

“Because the South American variant of the VPS13A gene is also found in other golden-wing populations, some individuals from populations that currently breed in the Great Lakes might be able to change their migration strategy,” says Toews. “Though it is still hypothetical, that would mean recolonization of Appalachia by golden-wings is at least within the realm of possibility.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library