Fantastic Journeys: Shorebirds Are Next-Level Athletes

By Nathan R. Senner and Alison Johnston

Bar-tailed Godwits by Gerrit Vyn. September 19, 2018From the Autumn 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Shorebirds are the undisputed marathon champions among migratory birds. About 20 species of shorebirds have been recorded making nonstop flights longer than 5,000 kilometers, or 3,100 miles—about the distance from Boston to San Francisco. No other species of migratory bird has been recorded completing a nonstop flight longer than 4,000 km.

The longest known shorebird flights—about 12,000 kilometers and nine days in length—belong to the Bar-tailed Godwit during its migration from Alaska to New Zealand. But even small shorebird species make epic flights. The Semipalmated Sandpiper, which at about 22 grams weighs less than an apple, makes nonstop flights of 5,300 kilometers from Canada to South America—that’s the aerial equivalent of completing 126 consecutive marathons.

To accomplish these incredible migratory feats, shorebirds are legendary gorgers. Red Knots stopped over in the Delaware Bay on migration feast on horseshoe crab eggs and more than double their body mass in just three weeks. Not all of that food goes toward fuel. Research on Whimbrels stopped over in Chesapeake Bay showed that the protein from a feast of crab eggs went directly into producing eggs when the Whimbrels arrived on their breeding grounds in Churchill, Manitoba, just days later.

In this way, shorebirds rely on habitat across hemispheres, which means shorebird conservation requires international efforts. Protecting important habitat for a single shorebird species could unite a native Inuit community in Alaska, a California rice farmer in the Central Valley, and a Mexican fishing village in a shared goal. Shorebirds are a unique opportunity for conservation diplomacy—a chance to bring the peoples of the Americas together for birds.

How Do They Manage Such Extreme Endurance?

Flight is one of the most energetically costly forms of locomotion, with long-distance flight being especially expensive and requiring a suite of incredible physiological adjustments. Scientists are still just beginning to understand the incredible athletic feats of shorebirds, only recently discovering that some shorebirds migrate at the altitudes of jet-liners, while others fly their entire migrations at speeds approaching 100 kilometers per hour (or more than 60 mph). Future research will continue to elucidate what makes it possible for shorebirds to push the boundaries of what humans think is possible. At present, here’s what we know about how they do it:

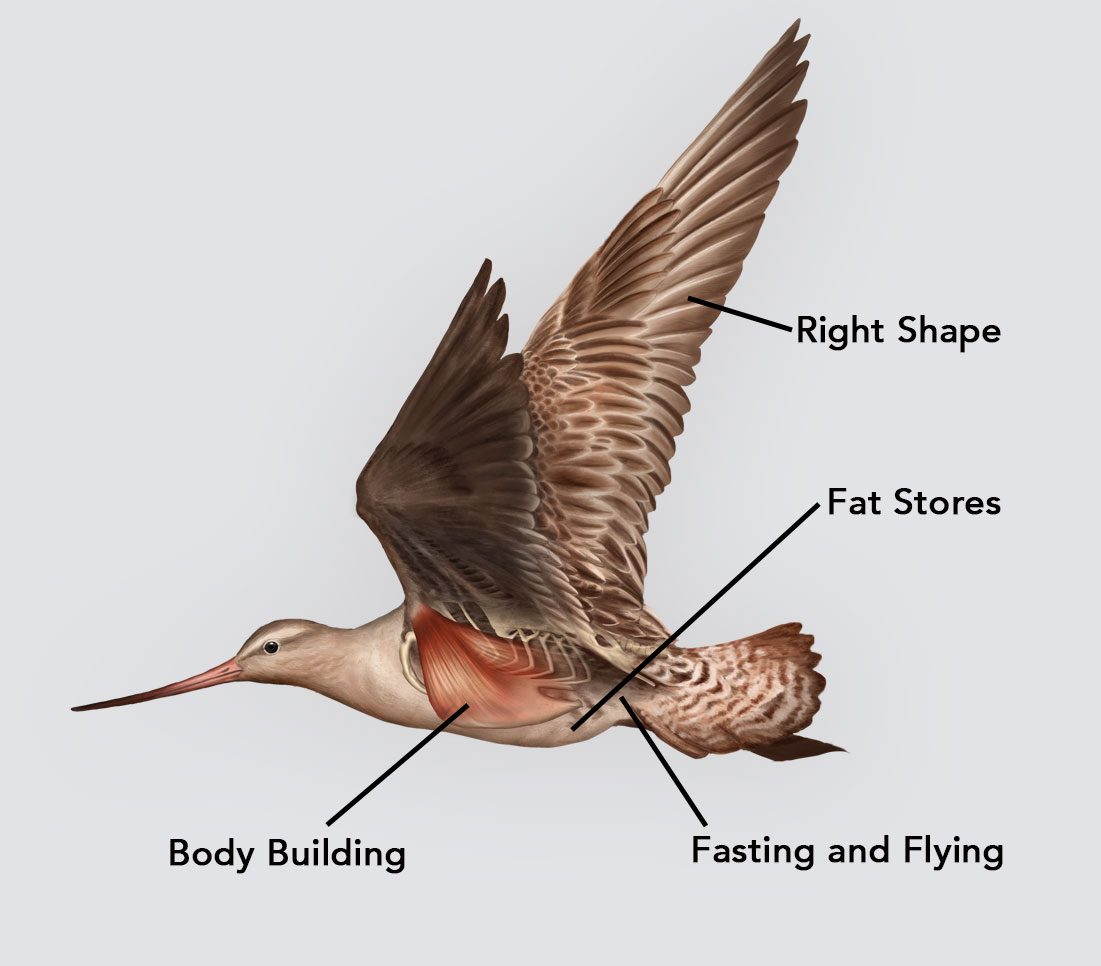

They Have the Right Shape

Long pointed wings allow shorebirds to efficiently carry heavy loads, while a long, sleekly shaped body helps them minimize drag while in the air. This aerodynamic design allows shorebirds to fly at high speeds while migrating, enabling them to travel long distances while maintaining their heading in the face of crosswinds that threaten to blow them off course. Shorebirds’ body shapes may also enable them to climb to high altitudes more easily, where they can avoid high air temperatures and find favorable tailwinds.

They Build Up Fat Stores

Unlike humans, birds rely predominantly on fat to power their endurance exercise. Fat holds significantly more energy per unit than carbohydrates. Before departing on their migration from Alaska to New Zealand, Bar-tailed Godwits more than double their body weight. Most of that added weight comes in the form of fat, which comprises up to 55 percent of a departing godwit’s mass.

They can Fly While They Fast

Bar-tailed Godwits burn about a calorie over every 3 km of flight, but they don’t add back any calories over their 12,000-km flights—fasting for the entire two weeks of their fall migration. Upon arrival in New Zealand, the Bar-tailed Godwits weigh about half of what they did when they departed Alaska, as they have burned through nearly all of their fat.

They’re Incredible Body-Builders

Because they grow so heavy for their migrations, shorebirds also need to bulk up their flight and respiratory muscles to help carry all that weight and pump blood to supply all of the extra tissue. Bar-tailed Godwits nearly double the size of their pectoralis (breast) muscles, as well as the size of their heart and lungs. To accommodate their musclebound migratory physique, shorebirds shrink the organs they don’t need, reducing the size of their stomach and gizzard prior to departure.

What Would It Take for a Human to Measure Up?

Cyclists competing in the Tour de France burn more than 8,000 calories per day in order to maintain metabolic rates five times higher than their base metabolic rates. Bar-tailed Godwits migrating from Alaska to New Zealand must be able to maintain metabolic rates more than nine times higher than their basal rates for over nine days. In order to duplicate the feats of these migratory shorebirds, cyclists would have to nearly double that energetic output—and do so without food or water. The average professional cyclist weighs 160 lbs and maintains 2 to 3 percent body fat. Were they to prepare for a Bar-tailed Godwit’s migration, they would need to put on more than 160 additional lbs, of which at least 126 lbs would need to be fat. Can you imagine a 320-pound cyclist (the size of former NFL defensive lineman William “The Refrigerator” Perry) pedaling through the French Alps?

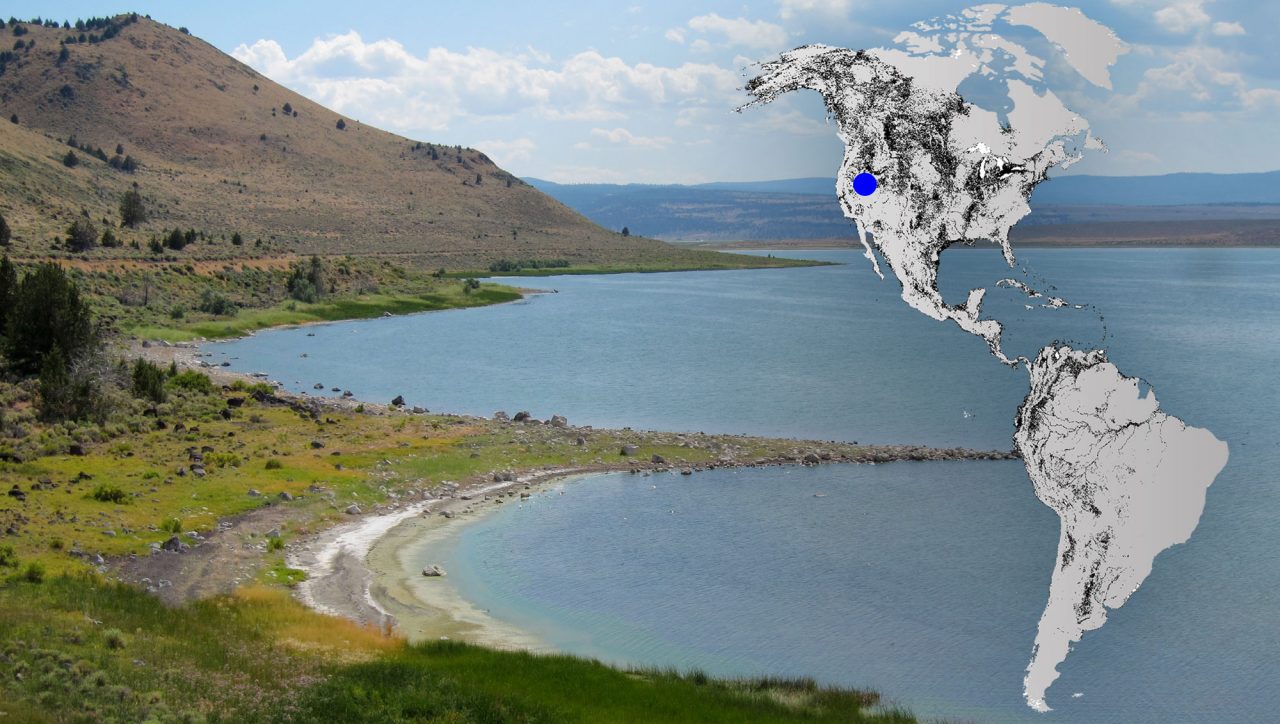

eBird Analysis: Finding the Habitats Shorebirds Use Most

Prairie Pothole Region. The prairie states and provinces are often called America’s "Duck Factory," but prairie wetlands are also critical for many shorebirds, especially during migration. A recent study estimated that more than 7 million shorebirds use prairie habitat during spring migration. Prairie grasslands by Wing-Chi Poon/Wikimedia Commons.

Great Basin Saline Lakes. The saline lakes of the Great Basin—such as Great Salt Lake in Utah, Mono Lake in California, and Lake Abert in Oregon—are major stopover areas for migratory shorebirds. Lake Abert hosts flocks of more than 250,000 Wilson’s and Red-necked Phalaropes in autumn. Lake Abert by Miguel Vieira/Flickr Creative Commons.

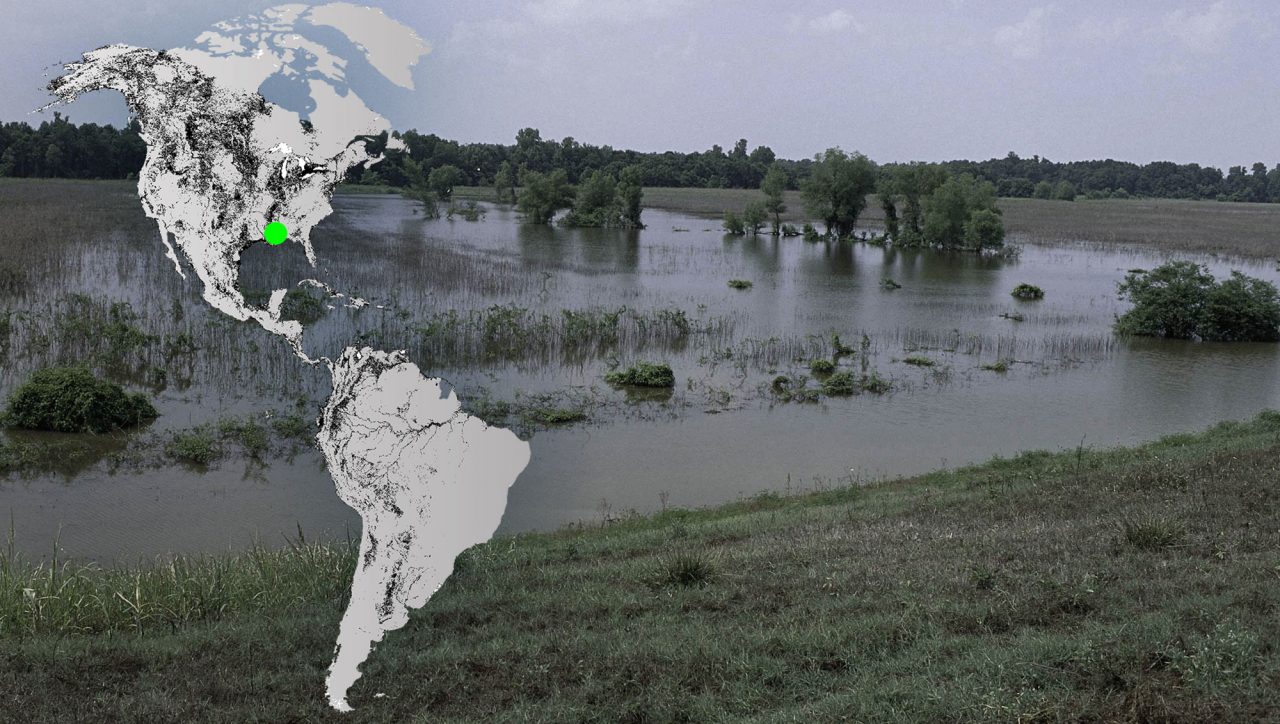

Lower Mississippi River Valley. The river-bottom forests of the Lower Mississippi have been heavily converted to row-crop agriculture, and even aquaculture (fish ponds). But these areas can still serve as important shorebird habitat. Drained aquaculture ponds and flooded crop fields can host high densities of shorebirds during fall migration, offering farmers a chance to participate in conservation-incentive programs in between harvests. Panther Swamp by Karen Hollingsworth/USFWS.

Amazon River Basin. Who would have thought that Hudsonian Godwits—those denizens of the windswept, frozen tundra of Hudson Bay—spend an average of nine days in the middle of the Amazon during fall migration? The Amazon provides crucial stopover habitat for several migratory shorebird species. Where do the shorebirds stop among all the trees? Along the shores of lakes and rivers nestled between patches of forest. Ecuadorian Amazon by Dallas Krentzel/Flickr Creative Commons.

In the slideshow images above, the map depicts an eBird model of the densest concentrations of 41 shorebird species throughout the year in the Western Hemisphere. While shorebirds are often thought of as creatures of ocean coastlines, some of the habitats that pop out in this eBird model are inland areas—the saline lakes of the West, the Prairie Pothole Region, the Lower Mississippi River Valley, and the Amazon River Basin. From the High Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, shorebirds rely on a network of habitats throughout the Americas to sustain their annual life cycles.

Source: Important sites for 41 shorebird species that breed in North America were generated using eBird estimates of bird abundance and an algorithm to identify sites that often hold high numbers of a variety of shorebird species.

Three Species, Three Ways to Use the Hemisphere

Hudsonian Godwit: A North–South Extremist

A large shorebird with a long, slightly upturned bill; breeds at the top of the world (in the Arctic) and winters at the bottom (in southern South America). Remote breeding and wintering grounds made Hudsonian Godwit migration a mystery for much of the last century, but scientists deployed tracking devices to figure out how these gangly shorebirds execute their hemisphere-spanning flights.

Power Meals. Godwits need high-quality habitat—sedge marshes and intertidal mudflats teeming with insect larvae—to fuel their migration. By lift-off, the Hudsonian Godwit weighs twice its normal weight, with half its body mass being fat for fuel.

All-You-Can-Eat Rest Stops. For spring migration, a Hudsonian Godwit flies the distance of three Tour de France courses laid out back-to-back over 170-plus consecutive hours. During a stopover in Nebraska on the way to Alaska, godwits put on as much as 3 percent of their body mass in fat each day. That’s like a 200-pound person chowing down on cheeseburgers to put on an additional 6 pounds of weight every day.

A Critical Island. Hudsonian Godwits that breed in Alaska spend winter on Chile’s Chiloé Island. Aquaculture operations currently threaten many intertidal habitats on Chiloé, and sea-level rise may soon affect these habitats as well. Godwit conservation efforts should include reducing disturbance in intertidal habitats and protecting roost sites.

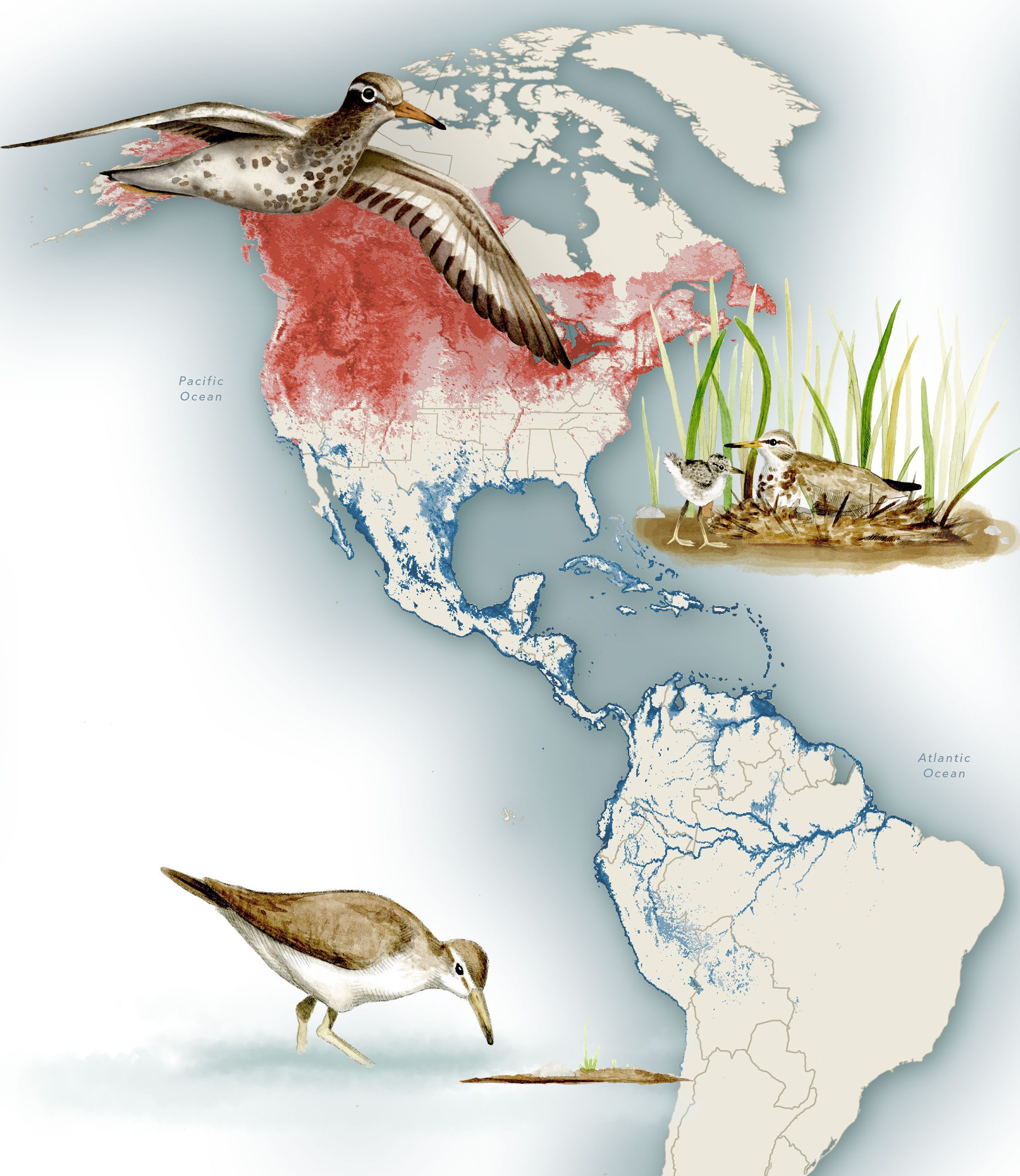

Spotted Sandpiper: Fanning Out Across Both Americas

A great ambassador for North America’s shorebirds; dapper and handsome with bold dark spots on a bright white breast. Charismatic, too, with a characteristic teetering motion that has earned them many nicknames, such as teeter-peep and tip-tail. The most widespread breeding sandpiper species in the U.S.A. and Canada. Migrate to spend winter along the coasts in North America or on beaches, mangroves, and rainforests in Central and South America.

Ladies First. Female Spotted Sandpipers arrive at the breeding grounds earlier than males in spring, and she is the one who establishes and defends the territory. She also may have more than one mate. Spotted Sandpiper females may lay eggs for up to three different males in a breeding season. The males, on the other hand, take the primary role in parental care, incubating the eggs and taking care of the young.

Where There’s Water. During migration Spotted Sandpipers can show up anywhere there is water, including lakes, rivers, marshes, and estuaries and ocean beaches. During fall migration, large numbers of Spotted Sandpipers have been seen gathering on sandy beaches in Venezuela.

Spreading Out for the Winter. Spotted Sandpipers have one of the largest nonbreeding distributions of any Western Hemisphere shorebird. On the Pacific Coast, they can be found from British Columbia to Peru, while on the Atlantic Coast they range from Maine to Argentina. Many Spotted Sandpipers also winter in the Amazon Basin.

Fly South. Spotted Sandpipers begin to exhibit restless behavior associated with migration, also called zugunruhe, as high-pressure fronts arrive in late summer and fall. Decreasing photoperiod (or day length) also appears to stimulate the Spotted Sandpiper’s molt into new feathers for fall migration.

Piping Plover: Caribbean Commuter

Prone to hiding in plain sight, with sandy gray backs that blend into sandy shores on the ocean and lakes. Most people don’t even notice plovers on a beach until these big-eyed shorebirds scurry down the sand on their orange legs. Nest in soft sand away from the water’s edge. Endangered due to habitat loss, disturbance, and predation. Conservation efforts have helped stabilize populations along the Atlantic Coast, but the Great Lakes breeding population still hasn’t yet reached its Endangered Species Act recovery goal of 150 breeding pairs.

Home Sweet Home. Despite migrating hundreds of miles from their wintering areas, many Piping Plovers return to the same beaches every year to breed. Individuals that return to breed with the same mate often nest within 130 feet of the previous nest site.

Midwesterners and East Coasters. There are three main Piping Plover breeding populations—on the Great Plains, along the Great Lakes, and along the Atlantic Coast—that remain separated on migration.

Bahamas Getaway. Everyone needs a secret beach hideout. Researchers recently discovered that more than one-third of the Atlantic Piping Plover breeding population spends winter in the Bahamas. This exciting discovery led to a major conservation victory with the declaration of the Joulter Cays National Park by the Government of The Bahamas in 2015.

Do Not Disturb. People love to play at the beach, but if plovers are present, the birds need their quiet space. A recent study found that Piping Plovers wintering on heavily used beaches had 7 percent lower body weights and 13 percent lower survival rates than plovers overwintering in less visited areas.

About the Authors

Nathan Senner studied Hudsonian Godwits for his PhD at Cornell University and has worked with shorebirds across the globe over the past 20 years. He was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Montana and became an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina in January 2019.

Nathan Senner studied Hudsonian Godwits for his PhD at Cornell University and has worked with shorebirds across the globe over the past 20 years. He was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Montana and became an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina in January 2019. Alison Johnston is an ecological statistician who enjoys number-crunching bird datasets to discover more about the natural world. She is an eBird data analyst based at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

Alison Johnston is an ecological statistician who enjoys number-crunching bird datasets to discover more about the natural world. She is an eBird data analyst based at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

Special thanks to the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for funding the large-scale eBird data analysis project to produce and refine distribution and abundance models for shorebirds. The project will help scientists identify and move forward on conservation work to protect the most important shorebird habitats in the Western Hemisphere.

Special thanks to the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for funding the large-scale eBird data analysis project to produce and refine distribution and abundance models for shorebirds. The project will help scientists identify and move forward on conservation work to protect the most important shorebird habitats in the Western Hemisphere.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library

Nathan Senner studied Hudsonian Godwits for his PhD at Cornell University and has worked with shorebirds across the globe over the past 20 years. He was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Montana and became an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina in January 2019.

Nathan Senner studied Hudsonian Godwits for his PhD at Cornell University and has worked with shorebirds across the globe over the past 20 years. He was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Montana and became an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina in January 2019. Alison Johnston is an ecological statistician who enjoys number-crunching bird datasets to discover more about the natural world. She is an eBird data analyst based at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

Alison Johnston is an ecological statistician who enjoys number-crunching bird datasets to discover more about the natural world. She is an eBird data analyst based at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.