Decoding Feathers for Cambodian Vulture Conservation

By Gustave Axelson

July 15, 2012

Yula Kapetanakos had been a vegetarian since she was 17, so she never dreamed that, as a Ph.D. candidate at Cornell University, she would stand by during the slaughter of a cow. Or pick through the rib cage of a dead animal to retrieve vulture feathers. Or ride for three hours on the back of a motorbike, all the while holding a live chicken for dinner.

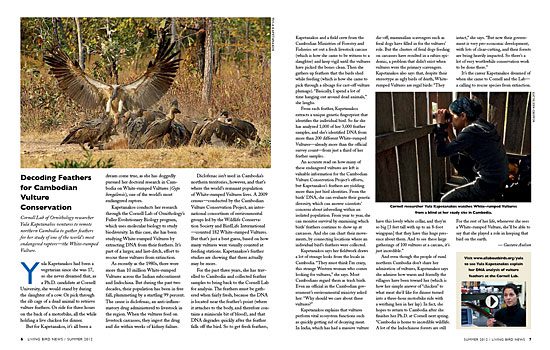

But for Kapetanakos, it’s all been a dream come true, as she has doggedly pursued her doctoral research in Cambodia on White-rumped Vultures (Gyps bengalensis), one of the world’s most endangered raptors.

Kapetanakos conducts her research through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology program, which uses molecular biology to study biodiversity. In this case, she has been studying White-rumped Vultures by extracting DNA from their feathers. It’s part of a larger, and last-ditch, effort to rescue these vultures from extinction.

As recently as the 1980s, there were more than 10 million White-rumped Vultures across the Indian subcontinent and Indochina. But during the past two decades, their population has been in free fall, plummeting by a startling 99 percent. The cause is diclofenac, an anti-inflammatory drug administered to livestock in the region. When the vultures feed on livestock carcasses, they ingest the drug and die within weeks of kidney failure.

Diclofenac isn’t used in Cambodia’s northern territories, however, and that’s where the world’s remnant population of White-rumped Vultures lives. A 2009 census—conducted by the Cambodian Vulture Conservation Project, an international consortium of environmental groups led by the Wildlife Conservation Society and BirdLife International —counted 182 White-rumped Vultures. But that’s just a best guess, based on how many vultures were visually counted at feeding stations. Kapetanakos’s feather studies are showing that there actually may be more.

For the past three years, she has travelled to Cambodia and collected feather samples to bring back to the Cornell Lab for analysis. The feathers must be gathered when fairly fresh, because the DNA is located near the feather’s point (where it attaches to the body, and therefore contains a miniscule bit of blood), and that DNA degrades quickly after the feather falls off the bird. So to get fresh feathers, Kapetanakos and a field crew from the Cambodian Ministries of Forestry and Fisheries set out a fresh livestock carcass (which is how she came to be witness to a slaughter) and keep vigil until the vultures have picked the bones clean. Then she gathers up feathers that the birds shed while feeding (which is how she came to pick through a ribcage for cast-off vulture plumage). “Basically, I spend a lot of time hanging out around dead animals,” she laughs.

From each feather, Kapetanakos extracts a unique genetic fingerprint that identifies the individual bird. So far she has analyzed 1,000 of her 3,000 feather samples, and she’s identified DNA from more than 200 different White-rumped Vultures—already more than the official survey count—from just a third of her feather samples.

An accurate read on how many of these endangered vultures are left is valuable information for the Cambodian Vulture Conservation Project’s efforts, but Kapetanakos’s feathers are yielding more than just bird identities. From the birds’ DNA, she can evaluate their genetic diversity, which can answer scientists’ concerns about inbreeding within an isolated population. From year to year, she can monitor survival by examining which birds’ feathers continue to show up at carcasses. And she can chart their movements, by connecting locations where an individual bird’s feathers were collected.

Kapetanakos says her fieldwork draws a lot of strange looks from the locals in Cambodia. “They must think I’m crazy, this strange Western woman who comes looking for vultures,” she says. Most Cambodians regard them as trash birds. Even an official in the Cambodian government’s environmental ministry asked her: “Why should we care about these vultures?”

Kapetanakos explains that vultures perform vital ecosystem functions such as quickly getting rid of decaying meat. In India, which has had a massive vulture die-off, mammalian scavengers such as feral dogs have filled in for the vultures’ role. But the clusters of feral dogs feeding on carcasses have resulted in a rabies epidemic, a problem that didn’t exist when vultures were the primary scavengers. Kapetanakos also says that, despite their stereotype as ugly birds of death, White-rumped Vultures are regal birds: “They have this lovely white collar, and they’re so big [3 feet tall with up to an 8-foot wingspan] that they have this huge presence about them. And to see these large gatherings of 100 vultures at a carcass, it’s just incredible.”

And even though the people of rural northern Cambodia don’t share her admiration of vultures, Kapetanakos says she admires how warm and friendly the villagers have been toward her (which is how her simple answer of “chicken” to what meat she’d like for dinner turned into a three-hour motorbike ride with a writhing hen in her lap). In fact, she hopes to return to Cambodia after she finishes her Ph.D. at Cornell next spring. “Cambodia is home to incredible wildlife. A lot of the Indochinese forests are still intact,” she says. “But now their government is very pro-economic development, with lots of clear-cutting, and their forests are being heavily impacted. So there’s a lot of very worthwhile conservation work to be done there.”

It’s the career Kapetanakos dreamed of when she came to Cornell and the Lab— a calling to rescue species from extinction. For the rest of her life, whenever she sees a White-rumped Vulture, she’ll be able to say that she played a role in keeping that bird on the earth.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library