Book Review: Birds of Paradise, by Tim Laman and Edwin Scholes

Review by Stephen J. Bodio

October 15, 2013

Birds-of-Paradise are mysterious. They are perhaps the most startling examples of Darwin’s “Endless Forms”; although they are relatives of crows and jays, they mask this with unlikely colors and structures, which they display in dances like no other performances on earth. What could be more alien than the male King of Saxony Bird-of-Paradise: starling-sized, with two-foot-long streamers made of what look like plastic flags coming out of his head? What about the dancing Superb Bird-of-Paradise, which turns itself into a bouncing horror mask shaped like a paper plate?

Western scientists and artists have been trying to imagine these birds since the first footless specimens arrived in Europe in the 1500s. To see them, you must be intrepid. New Guinea is the second-largest island in the world, and one of the wildest places we have left, roadless and wet, with an intricate fractal vertical landscape creating myriad island habitats. It took the combined efforts of two scientist-photographer-adventurers (Tim Laman and the Cornell Lab’s Ed Scholes) to document some of these dances in photographs for the first time. Their narrative hints at how hard it was.

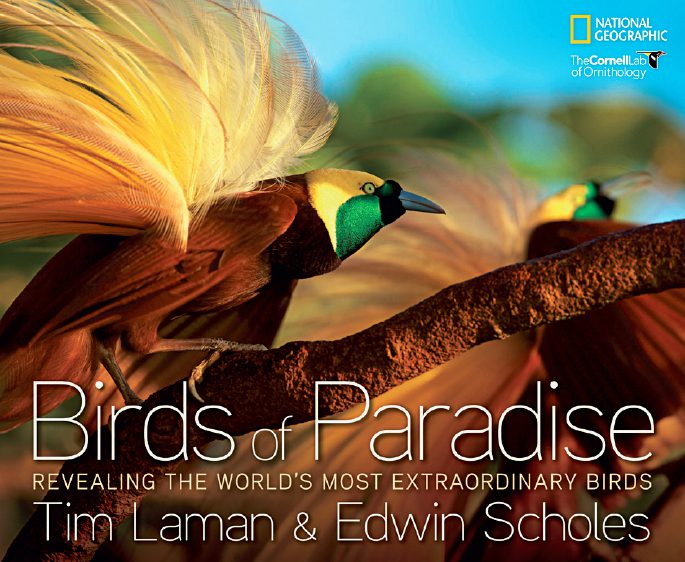

The words and the science are good, the photos incredible. Their documentation is impeccable, but the photos make the book. Some are close-ups, some distant views of displaying birds above the canopy. Some just glimpses—a spiral tail feather, a head with a glowing eye, a cape with iridescent feathers. My favorites are the ones that finally reveal what the males are doing in their dances, unimagined and unlikely shapes and movements that artists were still getting wrong in the 1950s. The three most amazing to my mind are not the gaudy “plume birds,” such as the golden Greater Bird-of-Paradise, but dark birds that transform themselves into shapes not remotely birdlike. Wahnes’s Parotia turns himself into something that resembles, from the female’s point of view, a spinning oldfashioned record disk. The Black Sicklebill becomes an amplifier shaped like a sine wave, wings joined over an invisible head to project its call. The little Superb Birdof-Paradise turns the disk vertical, with shining blue eyespots and a grinning mouth, and hops up and down. Again, nothing birdlike is visible.

These three are the oddest, and my favorites, but they should not take away from the improbable glowing primary colors of the Wilson’s Bird-of-Paradise, its bare blue skull adorned with a black feathered cross; the shimmering hula skirts of the plume birds; the ridiculous white tail streamers of the Ribbon-tailed Astrapia; the racquet-tipped wire tail of the little red King; or the erect white plumes of the Wallace’s Standardwing, the first one portrayed correctly since Alfred Russel Wallace saw it in 1869.

Laman and Scholes are the first I know of who photographed all of the others, though a few good artists, such as William Cooper, did them correctly in the 1970s. The book contains species accounts and lines of descent, and some good photos of the people of New Guinea, who dance like birds cloaked in bird feathers. It’s all worth reading, but this is one book you’re going to buy for the photographs.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library