Birding by Kayak in California’s Channel Islands

by Chuck Graham

July 15, 2009

Stranded on Santa Barbara Island, more than 40 miles off the Southern California coast, I lost count of how many times I kayaked around the tiny, one-square-mile islet. Howling northwest winds thwarted my scheduled boat transportation to the mainland, extending my four-day trip into a wind-whipped ten. But I was grateful to be here and made the most of the pelagic birding opportunities in this remote, lonely place.

During one of my laps, I found myself on the south side of the island again at Cat Canyon—a craggy gulch with thousands of raucous California sea lions. This time, the pinnipeds weren’t the only wildlife worth watching, as I came bow to beak with a tiny Xantus’s Murrelet.

Santa Barbara and Anacapa islands hold the largest rookeries of these hardy little seabirds in the United States. Showing no fear at all among the bobbing sea lions, hovering Western Gulls, and capping seas, the solitary murrelet swam steadily to calmer waters.

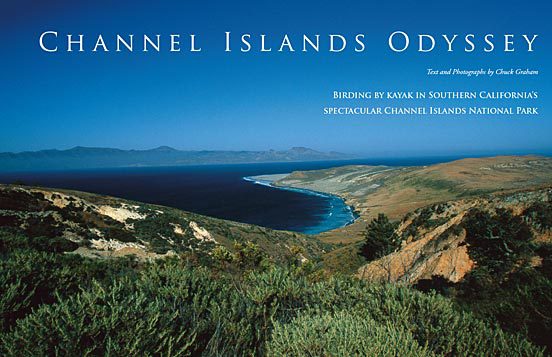

I have been visiting Channel Islands National Park since 1987 (and have been a kayak guide there since 2003), but I had never really explored and birded the volcanic archipelago in depth until 2001, when I circumnavigated the entire northern chain of Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel islands in a kayak—a 10-day, 175-mile trip. Paddling a kayak, I could reach all of the deserted coves, toothy grottos, and rocky, guano-covered pinnacles I couldn’t get to on foot, affording me more birding opportunities in this wave-battered landscape.

As a chain, the Channel Islands support a wide variety of wildlife, including about 60 landbird and 11 seabird species that nest in the national park. For some species, the archipelago offers the last remaining nesting habitat in an undisturbed natural environment.

The Channel Islands enjoy a year-round Mediterranean climate, but being prepared for any type of weather in the middle of the Santa Barbara Channel will definitely enhance your birding experience, especially on Anacapa, which has no cover from the northwest winds perpetually blowing there.

Santa Barbara and Anacapa Islands

Even though Santa Barbara and Anacapa islands are the smallest islets off the Southern California coast, they’re daunting to paddle around. Honeycombed cliffs rise 300 to 600 feet high on these islands, creating natural fortresses. Pockmarked with sea caves, fissures, alcoves, and crevices, they are virtual open-ocean condos for Pigeon Guillemots; Cassin’s Auklets; storm-petrels; Brandt’s, Pelagic, and Double-crested cormorants; Western Gulls; Peregrine Falcons; and Xantus’s Murrelets.

A campground on top of southeast Anacapa Island is the only base to begin a birding adventure, but it’s a good one. Because Anacapa has no beaches or other safe places to go ashore (except for a landing dock), a kayak is the best way to go. Even if you can’t paddle the entire six miles around the island, you’ll still see vast numbers of Brown Pelicans at their largest breeding colony in the western United States, along with other seabirds not far from the landing dock. Paddling offers the best opportunities to see murrelets, guillemots, and cormorants flying to and from their cliff nests, bringing food back to their hungry chicks. Western Gulls also nest here (bring your hard hat). Their nests are often in the middle of the trails, and their chicks run amuck across the entire island. Their parents tend to be very protective.

Santa Cruz Island

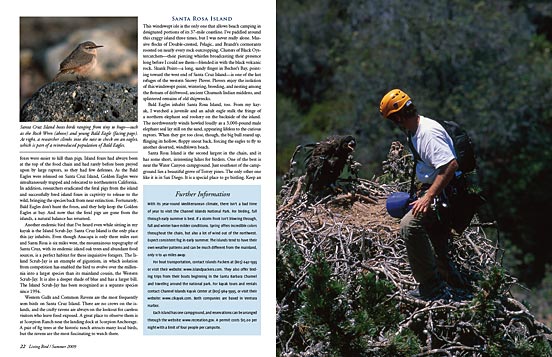

From 2002 to 2006, Santa Cruz—largest of the Channel Islands—has been a staging area for releasing Bald Eagles in an attempt to reestablish them in their historic range on the islands. The birds had been absent from the archipelago for more than half a century due to contamination by DDT and other pesticides that washed into the Southern California Bight off Los Angeles from the 1940s to the mid-1970s. The effects of DDT were far-reaching and had a serious impact on the food chain around the northern Channel Islands. Currently, the northern Channel Islands are not as exposed as the waters surrounding Catalina Island, where Bald Eagle restoration has been taking place since the 1980s. Sixty eagles have been released so far on Santa Cruz, about 35 of which have established territories across the chain. One nest in Pelican Canyon on Santa Cruz has been successful for the last three seasons. This is the first successful Bald Eagle nest in the national park since 1950, when a pair raised young on neighboring Santa Rosa Island.

Bald Eagles can be spotted from land, but using a kayak it’s easier to see them soaring above the coast, foraging for marine mammal carcasses, or perched on the sheer cliff-tops. The eagles are a keystone species and extremely important to the overall health of the unique ecosystem on Santa Cruz and the neighboring islands. During the Bald Eagles’ absence, Golden Eagles—which had rarely been seen on the islands—flew over from the mainland and nearly wiped out the island fox population on Santa Cruz Island and also on neighboring Santa Rosa and San Miguel islands. Initially lured by the numerous feral pigs on Santa Cruz Island, the Golden Eagles apparently soon concluded that the foxes were easier to kill than pigs. Island foxes had always been at the top of the food chain and had rarely before been preyed upon by large raptors, so they had few defenses. As the Bald Eagles were released on Santa Cruz Island, Golden Eagles were simultaneously trapped and relocated to northeastern California. In addition, researchers eradicated the feral pigs from the island and successfully bred island foxes in captivity to release to the wild, bringing the species back from near extinction. Fortunately, Bald Eagles don’t hunt the foxes, and they help keep the Golden Eagles at bay. And now that the feral pigs are gone from the islands, a natural balance has returned.

Another endemic bird that I’ve heard even while sitting in my kayak is the Island Scrub-Jay. Santa Cruz Island is the only place this jay inhabits. Even though Anacapa is only three miles east and Santa Rosa is six miles west, the mountainous topography of Santa Cruz, with its endemic island oak trees and abundant food sources, is a perfect habitat for these inquisitive foragers. The Island Scrub-Jay is an example of gigantism, in which isolation from competition has enabled the bird to evolve over the millennia into a larger species than its mainland cousin, the Western Scrub-Jay. It is also a deeper shade of blue and has a larger bill. The Island Scrub-Jay has been recognized as a separate species since 1994.

Western Gulls and Common Ravens are the most frequently seen birds on Santa Cruz Island. There are no crows on the islands, and the crafty ravens are always on the lookout for careless visitors who leave food exposed. A great place to observe them is at Scorpion Ranch near the landing dock at Scorpion Anchorage. A pair of fig trees at the historic ranch attracts many local birds, but the ravens are the most fascinating to watch there.

Santa Rosa Island

This windswept isle is the only one that allows beach camping in designated portions of its 37-mile coastline. I’ve paddled around this craggy island three times, but I was never really alone. Massive flocks of Double-crested, Pelagic, and Brandt’s cormorants roosted on nearly every rock outcropping. Clusters of Black Oystercatchers—their piercing whistles broadcasting their presence long before I could see them—blended in with the black volcanic rock. Skunk Point—a long, sandy finger in Becher’s Bay, pointing toward the west end of Santa Cruz Island—is one of the last refuges of the western Snowy Plover. Plovers enjoy the isolation of this windswept point, wintering, breeding, and nesting among the flotsam of driftwood, ancient Chumash Indian middens, and splintered remains of old shipwrecks.

Bald Eagles inhabit Santa Rosa Island, too. From my kayak, I watched a juvenile and an adult eagle stalk the fringe of a northern elephant seal rookery on the backside of the island. The northwesterly winds howled loudly as a 3,000-pound male elephant seal lay still on the sand, appearing lifeless to the curious raptors. When they got too close, though, the big bull reared up, flinging its hollow, floppy snout back, forcing the eagles to fly to another deserted, windblown beach.

Santa Rosa Island is the second largest in the chain, and it has some short, interesting hikes for birders. One of the best is near the Water Canyon campground. Just southeast of the campground lies a beautiful grove of Torrey pines. The only other one like it is in San Diego. It is a special place to go birding. Keep an eye out for subspecies of House Finch, Bewick’s Wren, Western Flycatcher, Spotted Towhee, and Loggerhead Shrike.

Spring flowers on Anacapa Island. Channel Islands National Park is a California treasure.

Anacapa Island is home to the largest breeding colony of Brown Pelicans in the western U.S.

A Rock Wren, one of Santa Cruz Islands regular nesting species.

A researcher checks a Bald Eagle nest while the eaglet's parents are away.

A petrified forest rises from sands where pygmy mammoths once roamed on San Miguel Island.

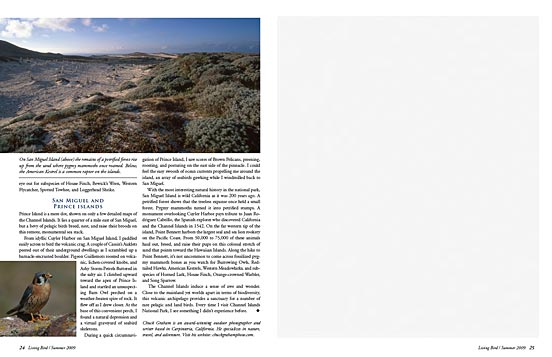

American Kestrels are common on the Channel Islands' open spaces.

San Miguel and Prince Islands

Prince Island is a mere dot, shown on only a few detailed maps of the Channel Islands. It lies a quarter of a mile east of San Miguel, but a bevy of pelagic birds breed, nest, and raise their broods on this remote, monumental sea stack.

From idyllic Cuyler Harbor on San Miguel Island, I paddled easily across to bird the volcanic crag. A couple of Cassin’s Auklets peered out of their underground dwellings as I scrambled up a barnacle-encrusted boulder. Pigeon Guillemots roosted on volcanic, lichen-covered knobs, and Ashy Storm-Petrels fluttered in the salty air. I climbed upward toward the apex of Prince Island and startled an unsuspecting Barn Owl perched on a weather-beaten spire of rock. It flew off as I drew closer. At the base of this convenient perch, I found a natural depression and a virtual graveyard of seabird skeletons.

During a quick circumnavigation of Prince Island, I saw scores of Brown Pelicans, preening, roosting, and posturing on the east side of the pinnacle. I could feel the easy swoosh of ocean currents propelling me around the island, an array of seabirds gawking while I windmilled back to San Miguel.

With the most interesting natural history in the national park, San Miguel Island is wild California as it was 200 years ago. A petrified forest shows that the treeless expanse once held a small forest. Pygmy mammoths turned it into petrified stumps. A monument overlooking Cuyler Harbor pays tribute to Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, the Spanish explorer who discovered California and the Channel Islands in 1542. On the far western tip of the island, Point Bennett harbors the largest seal and sea lion rookery on the Pacific Coast. From 50,000 to 75,000 of these animals haul out, breed, and raise their pups on this colossal stretch of sand that points toward the Hawaiian Islands. Along the hike to Point Bennett, it’s not uncommon to come across fossilized pygmy mammoth bones as you watch for Burrowing Owls, Red-tailed Hawks, American Kestrels, Western Meadowlarks, and subspecies of Horned Lark, House Finch, Orange-crowned Warbler, and Song Sparrow.

The Channel Islands induce a sense of awe and wonder. Close to the mainland yet worlds apart in terms of biodiversity, this volcanic archipelago provides a sanctuary for a number of rare pelagic and land birds. Every time I visit Channel Islands National Park, I see something I didn’t experience before.

Chuck Graham is an award-winning outdoor photographer and writer based in Carpinteria, California. He specializes in nature, travel, and adventure. Read more at his website.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library