Following Darwin’s Footsteps in the Falklands [slideshow]

By Tim Gallagher, editor of Living Bird magazine April 10, 2014

A pair of Rockhopper Penguins on New Island, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

A Brown Skua flies above an Imperial Shag colony, the Beagle Channel. © Tim Gallagher

The Falklands are hilly, windswept moorlands, resembling Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. © Tim Gallagher

A Magellanic Penguin peers out from its nest burrow, New Island, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

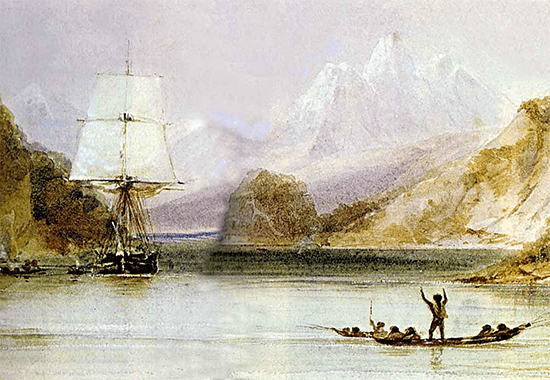

The HMS Beagle explores Tierra del Fuego in a painting by the ship's artist, Conrad Martens. Via Wikimedia Commons.

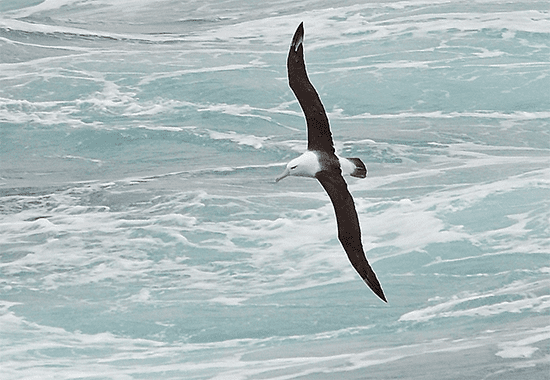

A Southern Giant-Petrel flies beside the ship en route to the Falklands. © Tim Gallagher

A nesting Brown Skua, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

A Black-browed Albatross feeds its chick, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

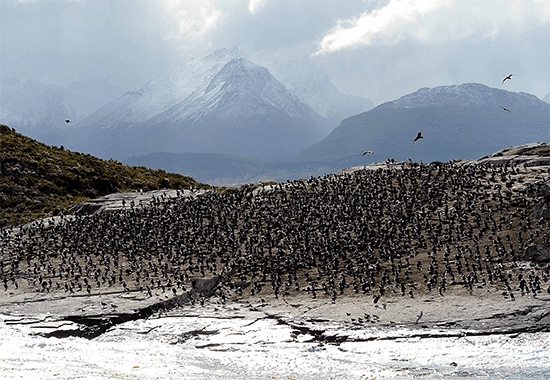

An Imperial Shag colony in Tierra del Fuego. © Tim Gallagher

Black-browed Albatrosses followed the ship for hours, soaring effortlessly in all kinds of weather. © Tim Gallagher

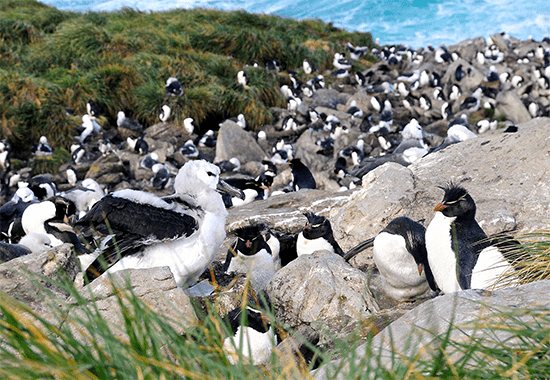

A young Black-browed Albatross with Rockhopper Penguins, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

A colony of Black-browed Albatrosses and Rockhopper Penguins, Falkland Islands. © Tim Gallagher

I couldn’t help thinking about Charles Darwin last month as I sailed from Ushuaia, at the very tip of Argentina, to the Falkland Islands, more than 400 miles away. He had made the same journey 182 years earlier in March 1832, and there were many reminders. The same snow-capped mountains of Tierra del Fuego I’d seen in a watercolor from Darwin’s five-year voyage loomed above us as we boarded the ship—and indeed, the strait we entered upon leaving Ushuaia was the Beagle Channel, named after the ship upon which Darwin traveled, the HMS Beagle.

Of course, Darwin had a much rougher passage on the Beagle—a cramped, 90-foot, wood-hulled, Royal Navy sailing ship. He shared his tiny cabin with two crewmen, and his bunk was so short he had to remove the drawers from a cabinet at the end of it each night to accommodate his feet. By contrast, I was traveling aboard the 367-foot National Geographic Explorer—a Lindblad/National Geographic cruise ship that carries 148 passengers in comfort.

The birds were spectacular right from the start. One high-flying speck soaring overhead quickly resolved itself into an adult Andean Condor in my binoculars—which was a complete surprise, though we were still in the Beagle Channel with the high mountains of Tierra del Fuego nearby. We passed a huge colony of Imperial Shags, sharing a rocky islet with fur seals, sea lions, and Brown Skuas, which would fly through the colony searching for prey or things to scavenge. But the seabirds we saw as we made our way out to the open ocean were even more spectacular. I stood at the stern of the ship for hours, watching them play with the wind above the swells—Black-browed Albatrosses, Wandering Albatrosses, Southern Giant-Petrels, Cape Petrels, shearwaters, storm-petrels, prions, and more.

The albatrosses were particularly impressive as they would alternately dive into the trough of a wave then swoop back up into the wind, using dynamic soaring to travel effortlessly for countless hours on their long, narrow wings. And they were always there, no matter how bad the weather or how rough the seas, making it all look so easy—which reminded me of a comment Darwin made in The Voyage of the Beagle: “Whilst the ship laboured heavily, the albatross glided with its expanded wings right up the wind.”

Some of the first birds we saw later as we landed our Zodiac boats on New Island in the Falklands were Striated Caracaras—or “Johnny rooks” as the islanders call them. “They are noisy,” explained Darwin, “uttering several harsh cries, one of which is like that of the English rook; hence the sealers always call them rooks.” The birds flew right up to us and followed us around. One tried to get into a camera bag I had set down on the sand. Darwin had warned about this: “These birds are very mischievous and inquisitive; they will pick up almost anything from the ground; a large black glazed hat was carried nearly a mile…. [They also took a compass] in a red morocco leather case, which was never recovered.”

Darwin was perhaps an unlikely candidate to be a naturalist aboard the Beagle, which had been sent by the Royal Navy on a two-year mission (which ended up stretching to five years) to chart the coast of South America. He was only 22 years old and had begun his education at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, studying to be a physician, as his father had been before him. But he had done poorly and found he had little interest in medical studies. All he wanted to do was hike around the countryside collecting shells, rocks, and various plant, insect, and animal specimens. So he left Edinburgh and completed a degree at the University of Cambridge. His father hoped he might become a country parson in some remote parish in England. (The parson-naturalist was a common figure in Victorian England, often seen with butterfly net in hand, studying the flora and fauna of his parish.) But going on the Beagle expedition—experiencing a wider world unlike anything he’d known in Britain—set his mind free and unleashed his genius.

The Beagle had an able captain in Robert FitzRoy, who although only 26 years old at the start of the expedition was already an accomplished explorer. It was his idea to bring along a geologist/naturalist, both to increase the scientific impact of the expedition and to provide him with intellectual company. Darwin was not the first choice—several more accomplished scientists had been approached first. But Cambridge professor John Stevens Henslow recommended him highly for the posting. And it was obvious when Fitzroy interviewed him that Darwin was highly intelligent, affable, and easygoing, and would make an excellent traveling companion.

New Island and the other two we visited (West Point Island and Carcass Island) during our two-day stay at the Falklands were treeless, with windswept hills and moorlands, highly reminiscent of Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, but with vastly different birdlife. It didn’t take long for us to see our first nesting penguins of the trip. Several Magellanic Penguins had nest burrows alongside the trail as we made our way up and over New Island to view a fur seal colony. The stocky, medium-sized penguins, with two distinctive black bands between their head and breast, stood amid the tussock grass or peeked from their nest burrows. But the highlight of my time in the Falklands was visiting two seabird colonies, shared by southern Rockhopper Penguins (delightful little yellow-crested penguins that jump over boulders and across cracks to get around); Imperial Shags (stunning blue-eyed cormorants with white breasts); and, best of all to me, Black-browed Albatrosses.

Both colonies were on steep, rocky slopes surrounded by tussock grass. The albatross nests were well-sculpted mounds, made of mud and stones, which the adults had shaped with their bills. Each nest contained a single large chick, nearly the size of an adult. The young albatrosses would flap their wings frequently, building strength in preparation for their first flight.

Occasionally, an adult albatross would return to the colony to feed its chick. As it came swooping in, riding the wind high above the colony and finally touching down, an amazing transformation took place: one of the most elegant flying creatures in the world instantly became a big, clumsy klutz of a bird, striding through the nest colony with its wings raised, being pecked at by annoyed Rockhopper Penguins as it passed. The adult would always go right to its own chick, disgorging a meal for the young bird before taking off and spending days or weeks foraging for more food in the open sea. Sadly, the Black-browed Albatross has been one of the bird species most commonly killed as bycatch in some longline fisheries. Recent changes in fishing equipment have helped reduce the level of bycatch considerably.

One of the animals Darwin saw, which is now missing, was the Falkland Islands wolf, or “warrah”—the only native land mammal on the Falklands. It became extinct in 1876. It really looked more like a large fox or dog than a wolf, but its closest living relative is the maned wolf of South America, from which it split more than six million years ago. It was a mystery for many years how the animal got to the Falklands, but scientists now speculate that it made its way there about 16,000 years ago when sea levels were lower, the islands were larger, and there might have been an ice corridor for them to cross.

Unfortunately for the warrah, it was incredibly unafraid of humans. “These wolves are well known [for their] tameness and curiosity, which the sailors, who ran into the water to avoid them, mistook for fierceness,” wrote Darwin. He correctly predicted its demise: “In all probability [it] will be classed with the Dodo, as an animal which has perished from the face of the earth.” He also noted that the wolves “from the western island were smaller and of a redder colour than those from the eastern”—which no doubt contributed to his later speculations on how island species, isolated from their ancestral species, evolve differing characteristics.

Leaving the Falklands after two days, we steamed eastward toward South Georgia Island, some 900 miles away. Stay tuned. I’ll be writing another blog post (and a Living Bird article) about South Georgia Island soon.

For more stories about birds of southern South America and the Southern Ocean:

- Exploring the Falkland Islands by Gary Kramer in Living Bird

- Birding the Drake Passage between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula, by Brian Sullivan

- Housekeeping Secrets of Swallows, Daisy Yuhas’ field work on Chilean Swallows breeding in southern Chile

- Pretty Good for a Five-Species Day, Hugh Powell goes birding in the Antarctic’s Ross Sea

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library