Bicknell’s Thrush Surveys Turn Up Illegal Clearing in Dominican Republic

April 19, 2013

Bicknell's Thrushes are rare Northeastern songbirds that winter in the Caribbean. Photo by Pedro Genaro Rodriguez.

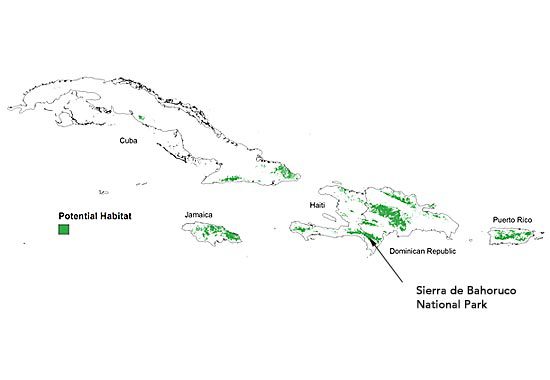

The entire population winters in the Caribbean, where potential habitat (green, from McFarland et al. 2013) is scarce. Map courtesy Yolanda Leon, Grupo Jaragua.

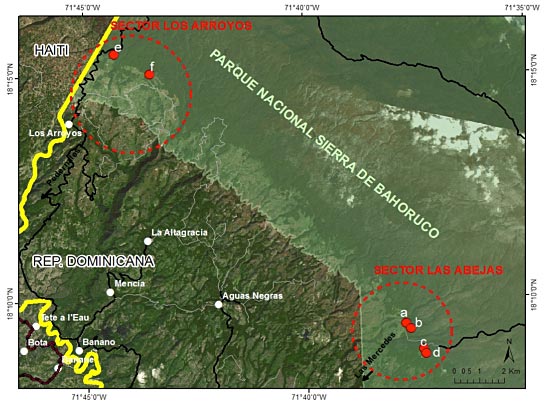

Fieldworkers surveying inside Sierra de Bahoruco national park discovered extensive illegal clearings. Photo by Yolanda Leon, Grupo Jaragua.

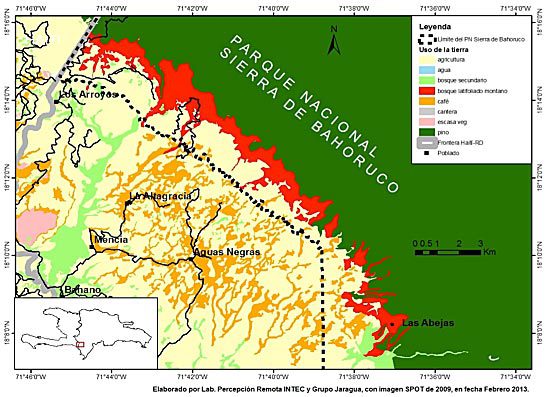

Bicknell's Thrushes live in cloud forest (red), which is threatened by agricultural expansion (yellow). Map courtesy Yolanda Leon, Grupo Jaragua.

Surveys for a rare North American songbird are shedding light on illegal forest clearing in the Dominican Republic, according to researchers from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies and Grupo Jaragua. The ongoing cutting in Sierra de Bahoruco National Park threatens some of Hispaniola’s last remaining undisturbed cloud forest. The park’s forests are a winter home to many North American migrants, refuge for 32 endemic Hispaniolan species, and an important source of freshwater for the people of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The deforestation was discovered as researchers surveyed for Bicknell’s Thrushes in the national park. These small, delicately spotted birds have flutelike songs and breed in mountaintop forests from New York and New England through Quebec and Nova Scotia. The entire population spends winters in the Caribbean, mostly on Hispaniola with lesser numbers in parts of Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico.

“It’s a cruel irony that as our Grupo Jaragua colleagues conducted surveys to document where Bicknell’s Thrush occur, they ended up documenting severe habitat loss in one of the species’ important strongholds,” said Chris Rimmer, director of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies. “They were literally counting thrushes while watching the cloud forest disappear.”

Because of severe population declines, Bicknell’s Thrush has been called the most threatened migrant songbird in northeastern North America and is under review for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act.

Cutting in the park has been going on since at least 2009, said Yolanda Leon of the Dominican nonprofit Grupo Jaragua. To date, an estimated 30 square miles of forest inside the park boundaries has been cleared. Surveys this winter indicated that clearing was creeping farther upslope and into the sensitive cloud forest.

“A lot of people get confused because they see a huge expanse of pine forest [higher in the park] and they say ‘Oh, the forest is fine,’” Leon said. “But we are looking at this fringe of forest that has a very specific band of occurrence, where the clouds meet the forest. It’s a very complex, beautiful forest, where you have a lot of migratory birds, and a lot of endemic birds.”

In November 2012, Leon and two colleagues, Esteban Garrido and Jesús Almonte, found high concentrations of wintering Bicknell’s Thrushes near the regions of Las Abejas and Los Arroyos on the mountain’s southern slopes. When they returned for more surveys in the first week of April, they discovered that patches of forest had been cleared to the ground. Some had already been planted with avocado, potatoes, beets, carrots, and beans. Elsewhere, cows grazed and makeshift ovens were turning felled timber into charcoal.

Deforestation is a major problem on Hispaniola, where economic conditions force many people to clear forests to collect firewood and grow crops. However, much of the current clearing appears to be a well-funded project of several influential Dominican landowners rather than subsistence agriculture, Leon said. They have instituted a sharecropping system, encouraging Haitian immigrants to clear and farm the land in return for a small share of the harvest.

Complicating the issue is the fact that the southern boundary of the park, though it appears on maps, is not marked on the ground. “A lot of people, they don’t want to get into trouble,” Leon said. “But if they don’t see a marker… they think they are just using fallow land.”

The cloud forest is one of the most important and threatened habitat types in Hispaniola. Sierra de Bahoruco is a part of the Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo UNESCO biosphere reserve and is a center of biodiversity for birds, amphibians, orchids, and other species. Beyond Bicknell’s Thrushes, other species that depend on the park’s forests are the globally endangered Black-capped Petrel and La Selle Thrush, and more than 30 unique species such as the Hispaniolan Parrot, Hispaniolan Trogon, Hispaniolan Crossbill, and Golden Swallow (more info in a BirdLife International PDF fact sheet).

Preserving intact forest is directly important for humans, too. “The montane forest is the sponge that captures moisture from the clouds. If we don’t have these forests, there’s no freshwater for Haiti and the Dominican Republic,” said Eduardo Iñigo-Elias, who coordinates the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Neotropical Conservation Initiative. The cloud forest of the Sierra de Bahoruco, specifically, feeds the Pedernales River, which forms part of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and supplies towns in both countries.

A separate pressure on the Sierra de Bahoruco’s drier, lower-elevation forests is the harvest of a shrub called guaconejo, or torchwood (Amyris spp.). Fragrant oils contained in the bark put this plant in high demand from the perfume industry, but few sources remain outside of parks, Iñigo-Elias said. Harvesters have begun to freely infiltrate the Dominican Republic’s protected lands, cut the trees, and bring them back to Haiti to ship to France, he said.

The Ministry of the Environment in the Dominican Republic is in charge of enforcing the regulations in national parks, Iñigo-Elias said. Representatives from Grupo Jaragua and Vermont Center for Ecostudies wrote to the ministry and met with staff to describe the situation and express their support for action to curtail the illegal activities. The main goal, according to Leon, is to begin negotiations with the landowners who are underwriting the clearing to arrive at an amicable resolution that protects the park’s lands without unfairly treating the Haitian immigrants hired to do the work.

In the meantime, Grupo Jaragua has launched a Friends of the Sierra de Bahoruco Facebook page (largely in Spanish) for people who want to keep up with developments. They also hope to raise funds to conduct a land occupation study so they can help make effective conservation interventions. The Cornell Lab is a longtime research partner of both Grupo Jaragua and Vermont Center for Ecostudies, and has trained Hispaniolan biologists in mist netting, acoustic surveys, and radio telemetry, and studied threatened species such as the Black-capped Petrel, Golden Swallow, and Bicknell’s Thrush. This work has been made possible by grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to the Cornell Lab.

“This is the wintering ground for so many species that we share with the people of Haiti and the Dominican Republic,” Iñigo-Elias said. “It’s an area of high humanitarian crisis given the lack of freshwater and the lack of fuel. And then on top of that, the last remaining resources are being cut for a few crops. I hope that all involved can come to an agreement that allows the park to do its job in protecting some of these last undisturbed remnants, and continue to provide ecosystem services to the local inhabitants.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library