After a Brutal Northeast Winter, Can Carolina Wrens Make a Comeback?

By Marshall J. Iliff

Carolina Wren by Marie-Ann D'Aloia via Birdshare. January 11, 2017From the Winter 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

It was just six months ago that summer bird watching in the Northeast was a predictable riot of color and bird song: orange-and-black Baltimore Orioles, Yellow Warblers like golden drops of sunshine along every pond and river edge, and swallows and swifts careening over fields and treetops. Some of our old friends are still hanging around our backyard bird feeders—Downy and Pileated woodpeckers, Black-capped Chickadees, and Northern Cardinals. But in Massachusetts, one member of that cast may be missing.

Where are the Carolina Wrens?

The Carolina Wren’s song is one of the more recognizable bird songs in eastern North America, an ebullient teakettle-teakettle-teakettle or cheer-cheery-cheery. But as its name suggests, it is mostly a southern species with a core range that runs roughly from east Mexico and Texas north to Chicago, east to Boston, and back south to Miami. Carolina Wrens are relative newcomers in the northern parts of their range, having expanded northward over the past 100 years due to a mix of factors that likely includes suburbanization, access to bird feeders, and a warming climate. The first Carolina Wren nest in Massachusetts was found in 1901. By the turn of the 21st century, it was a common species statewide.

But now, somewhat less common. The epic winter of 2015 took a heavy toll on Carolina Wrens. Coming up on two years later, they still haven’t regained their ground at the north of their range.

A Brutal Valentine

During Valentine’s Day weekend in 2015, temperatures across the Northeast plunged below zero. Boston hit –2°F, right in the midst of an epic snowy winter. By season’s end, the city had recorded 110 inches of snow, much of it falling in a series of blizzards.

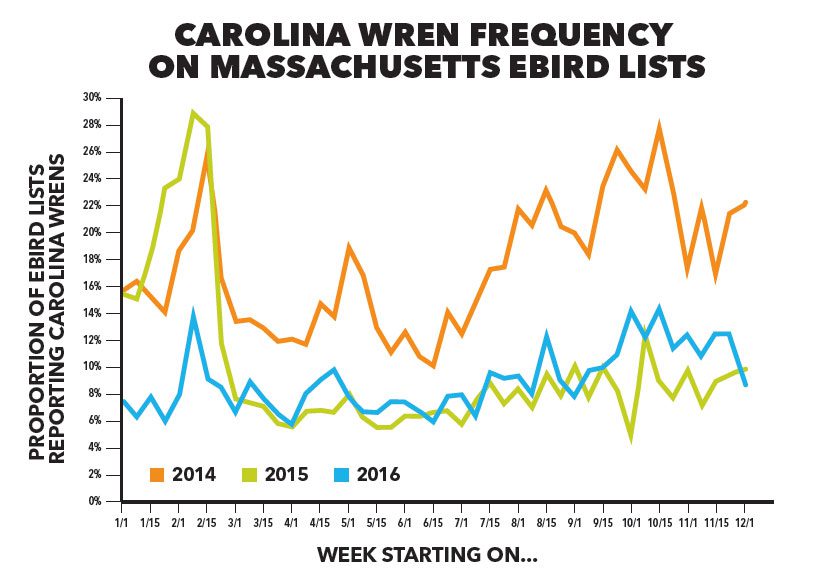

That bone-chilling weekend happened to coincide with the annual Great Backyard Bird Count, in which 150,000 bird watchers across North America turned out to count winter birds over a 4-day period. A look at three consecutive years of GBBC data—2014, the brutal winter of 2015, and the year after in 2016—shows the casualty count for Carolina Wrens. After peaking at almost 30 percent of eBird lists in Massachusetts in early February 2015, the frequency of Carolina Wren observations plummets by about half immediately following the Valentine’s Day cold snap—and it was still down by half last year. A look at the Christmas Bird Count data in Concord, Massachusetts, shows an even steeper decline—334 Carolina Wrens (0.865 per party/hour) observed in 2014–15 but only 90 in 2015–16 (0.233 per party/hour).

Carolina Wrens are especially sensitive to harsh winter weather as a species that feeds primarily near the ground; heavy snow and ice can easily cover their favorite areas for foraging. And Carolina Wrens are conspicuous and easy to count for backyard bird watchers, as they readily come to feeders. But other ground-foraging, nonmigratory species were also probably affected. A study conducted in southern Illinois in 1979 found that Winter Wrens, Hermit Thrushes, and Field Sparrows showed major population declines after a similar cold snap. That same study showed a complete loss of Carolina Wrens. All four of these species feed on or near the ground and were near the northern limit of their ranges.

How Long Does a Winter Hangover Last?

Local wren populations can bounce back in a couple of years, or it may take even longer, depending on the severity of the population reduction and how good breeding conditions are in successive summers. In areas with a complete extirpation, it may be a long time before they recolonize, given that most Carolina Wrens only disperse a few miles from where they hatch as nestlings.

After the wretched winter of 1917–18 it was four years before Carolina Wrens were common again in the Washington, D.C., area, according to the writings of Dr. Alexander Wetmore, an ornithologist and secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Then came another blizzard in January 1922, when Wetmore wrote: “A sudden heavy snowfall that … reached the unusual depth of 26 inches once more proved disastrous to the bird under discussion. Observations during February and March show that the Carolina Wren has again decreased in this region.”

Two decades later in 1948, another ornithologist associated with the Smithsonian, Dr. Arthur Cleveland Bent, wrote again about the tenuous state of Carolina Wrens in the North: “[Carolina Wrens] are not hardy birds, and the next severe winter may result disastrously for the adventurous pioneers. Most of their food is obtained on or near the ground, and when a deep fall of snow covers the ground for a long time and is accompanied by severe cold, most of the wrens succumb to cold and starvation.

“As a result we have alternating periods of scarcity in the northern states and probably shall never have permanent abundance.”

It’s hard to say whether or not Bent’s prediction will hold true in this century. While climate change may deliver warmer winter temperatures, there’s also a greater potential for more extreme weather events, including heavier snowfalls and wide temperature swings. The future for the northward march of Carolina Wrens continues to be unpredictable.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library