Measuring Tourism Impacts on the Oystercatchers of Kenai Fjords, Alaska

By Charles Eldermire April 15, 2008

My eyes strain, searching among the wave-cast cobbles of a rocky beach in Kenai Fjords National Park. Swaddled in orange, coated in rubber, and soaked through from the mists, we wait as our small boat carefully approaches shore, deep in a sheltered cove. Suddenly, a rapid kek-kek-kek-kekeddee call bursts forth from down the beach, and we spot our quarry: a Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani).

The boat driver cautiously noses the boat toward shore, wary for oncoming waves, as I jump from the bow into knee-deep water, giving the boat a solid push back to make sure it doesn’t get caught up in the waves breaking on shore. Ahead of me, the lone oystercatcher continues its tirade, and I trudge up the beach to scan for its mate.

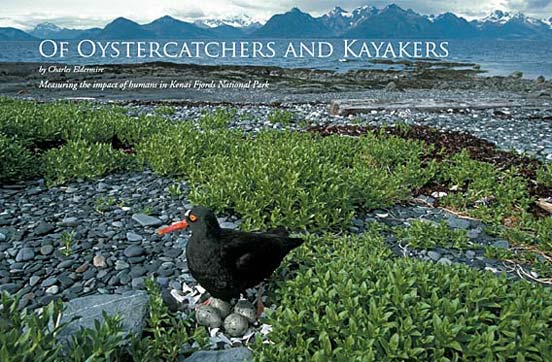

With its long, bright-orange bill, deep black plumage, and punk-rock-inspired toenails, you’d think it would be easy to spot this large shorebird, but oystercatchers are remarkably difficult to find when they are hunkered down on a nest, incubating eggs. If I’m lucky, I’ll spot a dark shadow among the stones and find the nest quickly. If not, I could spend an hour walking the high-tide line searching for an inconspicuous depression in the gravel, holding two or three eggs, perfectly camouflaged to resemble the larger stones surrounding them. But this time I spot the incubating adult quickly among the cobbles on this windswept beach and start gathering data. Within 15 minutes I’m back on the boat, returning to the blue glacial waters of Aialik Bay.

Such was life during my tenure as a research technician in 2005, working on a multiyear study to find out how much the presence of humans is affecting the nesting productivity of Black Oystercatchers in Kenai Fjords National Park. Sponsored by the Ocean Alaska Science and Learning Center, Kenai Fjords National Park, the University of Alaska–Fairbanks (UAF), and the U.S. Geological Survey’s Biological Resources Division, the research project was led by UAF master’s degree candidate Julie Morse, a seasoned field biologist with years of experience studying waterfowl in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

Although the park had collected data on the oystercatchers in past years, Morse’s study was the first to take an intensive look at the nesting productivity of the birds. Due to their small population size, low reproductive success, and limited distribution, Black Oystercatchers are listed as a species of high conservation concern by the Alaska Shorebird Working Group.

In Kenai Fjords, oystercatchers seem to prefer nesting on cobble beaches—which also happen to be some of the favorite camping areas of the kayakers who visit the park. When the study began, no one knew exactly what effect the campers might be having on the birds. And it was a potentially thorny issue, because it is difficult to quantify the consequences of various kinds of disturbance on the birds. It’s obvious in the case of a species like the Spotted Owl that human disturbance in the form of clear-cutting the forest has a major negative impact on the birds. But it’s more difficult to evaluate what effect hikers traveling through the backcountry might have on these owls. It’s a similar situation with the Black Oystercatchers: How do we evaluate the effect of these nonconsumptive users who come to the park to enjoy the wilderness experience?

Of course, human disturbance has been implicated in the declines of many species, from raptors and waterfowl to shorebirds and even passerines. However, these relationships are generally species-specific, and what affects one species may not affect another.

Although the effect that recreational kayakers might have on oystercatchers was largely unknown prior to Morse’s study, it was obvious that oystercatchers keep an eye on human interlopers and often become agitated. “As soon as a human arrives, a lot of oystercatchers get off their nests, so they’re not incubating their eggs,” says Morse. “They spend a lot of time yelling at the people in the area instead of foraging or incubating, so it’s a distraction for them.”

Another potential impact of people visiting the birds’ nesting areas is the accidental trampling of eggs. The eggs are highly camouflaged and difficult to see. An unwary kayaker could easily step on a nest by mistake. One day we saw a group of kayakers pull up on a beach we were observing and unwittingly head straight for a nest, eventually sitting down for lunch within a few feet of it.

From a management perspective, Morse hoped that her study would have a very pragmatic outcome—“to determine what level of human use is okay and will not affect oystercatchers and what level is too much.”

To measure productivity and what affects it, a scientist must be able to measure the factors that could potentially influence it. Many things can affect nest success. Predation often plays a major role in determining how many young nests produce. The suite of potential nest and nestling predators includes gulls, ravens, eagles, falcons, hawks, bears, deer, otters, mink, and wolverines.

“None of these predators are making a living off these oystercatcher eggs,” Morse explains, “but the eggs or the chicks are in such obvious spots that they are completely vulnerable to predation”—even though, for a human, finding a nest can seem almost impossible. Another factor might be the climate, with cold, wet conditions being unfavorable for nest survival. And in the case of Kenai Fjords, the actions of recreational users might also be harmful.

To address the issue of productivity, Julie and her crew monitored 35 to 39 breeding territories spread out across more than 175 kilometers of coastline in Aialik Bay and Northwestern Fjord during the breeding seasons from 2001 to 2005. We visited these territories periodically to check whether birds had begun nesting, and then revisited them to keep tabs on incubation, hatching, fledging, and failed nesting attempts. The researchers banded each pair with a unique combination of colored leg bands so that their nesting success could be charted from year to year. This approach is important with this species. Black Oystercatchers are a long-lived species, and animals that live longer usually have lower annual productivity because they will probably be able to come back the next breeding season and try again; shorter-lived species do not have this luxury.

The level of recreational use was more difficult to study, because kayakers, hunters, and fishermen are not required to have permits to enter the backcountry. Consequently, no official tally of backcountry users exists (although there is a voluntary permit system). Due to the difficulty and expense of arriving by boat from Seward, the number of campers is low compared with the parks in the Lower 48 states. But established campsites are scattered throughout the park (including sites on the nice cobbled beaches that oystercatchers prefer), and these sites are stocked with bear-proof food lockers. These lockers yielded a goldmine of information when they were fitted with a data-logger to record when the door was opened, providing a useful means for measuring how often the sites were used. Park rangers on patrol also gathered data about recreational users when they encountered them.

Finally, Morse set up an experiment that simulated the disturbances that campers might produce. She designed a protocol in which an observer would arrive at the beach, set up a tent, take two beach walks, and then break camp, all within an hour. These “disturbance” experiments were preceded by an hour of observation without disturbance, to get a baseline idea of how much time on average the adults incubate their nests. She compared the incubation durations from the disturbance trials with the undisturbed trials to see how much influence setting up a camp had on incubation.

After several seasons of study, a pattern began to emerge. The researchers monitored more than 500 eggs, which produced a total of only 51 chicks fledged, indicating that nest productivity was indeed abysmally low—roughly one chick fledged per pair every three years—but that’s fairly normal for Black Oystercatchers in other places. The in-depth behavioral disturbance experiments showed that oystercatchers incubate 39 percent less on average in response to the simulated camping, suggesting that kayakers could have an influence on nesting behavior. But actually, recreational use of these areas peaked well after the height of oystercatcher hatching, suggesting that kayakers and other recreational users probably have little effect on the majority of oystercatcher nesting attempts.

A much more natural factor—predation—accounted for most nest failures, causing approximately 65 percent of unsuccessful nests. Morse did find that the broods of oystercatchers nesting on rocky islands, away from the cobble beaches, had a far higher survival rate. This change of habitat hints at a possible tradeoff between the easy foraging of the cobble beaches and the relatively predator-free rocky islets.

Many living creatures can decrease the nest survival rate of the oystercatchers, but one ecological influence looms large—the sea. Oystercatchers nest right above the high tide line, and each year brings higher-than-normal tides during the spring full moons, which can flood the nests. Eggs that float out of the bowl for a short time and are returned to the nest by the adults when the water recedes seem to hatch fine. But sometimes spring tides combine with storms to flood the area completely, floating the eggs away and ending the nesting attempt. This was the most important ecological factor affecting nest survival in the study area. Extreme high tides were the direct cause of six percent of nest failures and may have caused the failure of an additional 23 percent.

So what does this mean for Black Oystercatchers in Kenai Fjords National Park? For now, not much of an overlap exists between recreational users and nesting oystercatchers, which suggests that kayakers do not have a high “direct” impact on the birds’ nesting success. But kayakers and oystercatchers tend to prefer the same beaches, so the impacts may be more subtle. Oystercatchers show high nest site fidelity regardless of recreational use, and they will probably continue to return to these beaches as the number of human visitors increases; the question is whether other animals will also be drawn to these beaches. No one knows whether the predator communities change at camping beaches, and because current levels of predation are already high this is a topic of concern.

The high nest-site fidelity of Black Oystercatchers also gives the Kenai Fjords park managers a straightforward management strategy. Most recreational use is concentrated around the food lockers, and campsites are grouped accordingly. One proactive option being considered by the park as a result of this study is simply to move the food lockers (and by extension, the campsites) farther away from the oystercatcher nesting areas, thus reducing the potential for disturbance.

Although park managers can take actions to increase oystercatcher productivity, there is one factor they cannot manage: the climate. Current global climate change predictions suggest that both the sea level and the frequency of storms will increase across the globe, though these effects will vary by region. These oystercatchers exist at the thin border between dark ocean waters and towering green mountains, and higher waves from an encroaching sea may portend a difficult future for the oystercatchers of the Kenai Fjords.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library