Louisiana report: A rookery in the Iron Banks (slideshow)

Text by Hugh Powell. Images by Benjamin Clock.

June 22, 2010

A Great Egret with fine breeding plumes on an island rookery in Bay California

Two Roseate Spoonbills and a Snowy Egret overlook a Great Egret in the rookery

Two adult Great Egrets keep watch over their four gangly young

Black-crowned Night-Herons nested low in the mangroves

Tricolored Herons, formerly called Louisiana Herons, are more abundant here than anywhere I've ever seen

Young Tricolored Herons are rusty purple above, with shoots of down still poking out between their feathers

Roseate Spoonbills are extravagantly pink, from crustaceans they sift from the mud

Young spoonbills are delicately pink, and somewhat unsure of how to wield their bills. These seemed to be practicing

Yesterday morning we were up early to visit the Iron Banks area east of the Mississippi River. We crossed by ferry, Capt. Iverson‘s fishing boat on a trailer behind his Suburban. The ferry dashed across the Big Muddy like a pedestrian crossing a highway—the whole trip took about five minutes. Then it was up over the levee, and down to the oyster docks of Pointe a la Hache, the seat of Plaquemines Parish, to put the boat in the water.

The red rising sun shimmied across the smooth blue water of Bay California, and it was as cool as it ever gets in June in Louisiana. Green fringes of saltmarsh grass marked islands in the distance, some with a curl of mangrove branches in the center. We steered for one dotted with white: a wading-bird rookery.

On the way over we saw about 50 laughing gulls convening over a riffle in the water. Speckled trout were below, harrying a school of shrimp toward the surface. About a third of the gulls were sitting on the surface while the rest wheeled and made low passes, occasionally dipping a bill to grab at prey. “There are times I’ll see that shrimp jump clear out of the water, and a Laughing Gull will catch him in mid-air,” Iverson said. “It’s a beautiful sight.”

The rookery was on an island formed from oyster shells and overgrown with two-foot-high saltmarsh grasses. A low rise in the island allowed mangroves a foothold, and the short trees were full of long-limbed wading birds and their chicks. We counted six species and a couple of hundred nests: Great and Snowy egrets, White Ibis, Black-crowned Night-Herons, Tricolored Herons, and Roseate Spoonbills.

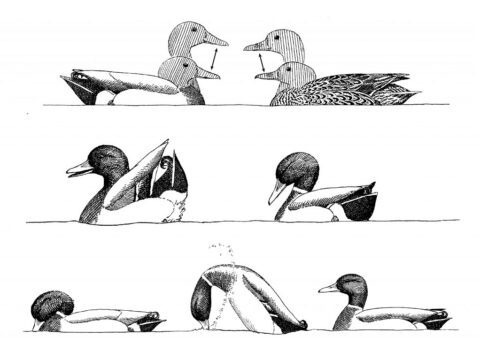

The nineteenth-century millinery trade threatened all these species for their bright feathers and elegant plumes. It was easy to see why, as shimmering plumes trailed in the morning breeze. Occasionally, a Snowy Egret would land in the front row of trees. Each time, fully grown young, noticeable by their greenish bills and yellowish legs, would pounce on the adult to be fed. A slow-motion chase ensued, the adult leading the chicks upwind, wings spread for lift and long legs feeling beneath them for perches. It seemed the same kind of learning-to-fly exercises that many songbirds lead their chicks on just after fledging. Eventually, a young bird caught its parent, locking bills with a dart of the neck, and began to yank.

A line of birds approached over the water—two Snowy Egrets trailed by five Roseate Spoonbills. The birds lined up on approach over the mangroves, and two spoonbills dropped down to nests. The others, almost like a subway pulling out of a station, picked up speed and headed for the next island.

Later, we saw four young Roseate Spoonbills testing out their brand-new, foot-long paddle-tipped beaks. These fledglings are palest, dinner-mint pink, without any of the valentine-card pink of adults.

“These islands, everyone calls them Iron Banks,” Iverson told us. “But they ain’t the real Iron Banks. The real Iron Banks no longer exist. They’re underwater about three feet on most tides.”

These Louisiana coastal marshes are disappearing. The centuries of accumulated sediment from the Mississippi settle or erode, as they have always done. But because of the levees on either side of the river, and the thousands of dams upstream, new sediment doesn’t flow in to replace it.

Scientists have measured the wetland loss at up to 39 square miles per year over recent decades. Old-time fishing captains can back those figures up. Iverson told me that even GPS navigation is tricky in the Delta, because so many islands and points, even ones mapped just a few years ago, are underwater. More worryingly for a boat captain, storms redistribute the sunken sand, filling in channels that were once navigable.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library