Looking Back on Wildlife Cleanup at a 1990 Oil Spill

Text and images by Tim Gallagher

May 19, 2010

For Tim Gallagher, editor of Living Bird magazine, the Deepwater Horizon oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico brought back sad memories of a spill cleanup he became involved in 20 years ago, in Bolsa Chica, California. He had arrived on the scene as a writer and photographer to document cleanup efforts—but the oiled birds were so heart-wrenching that he soon became a volunteer.

His story captures the sense of helplessness in the face of an enormous spill, as well as the small triumph of saving as many individual birds as we can, and that fierce, fond hope in the aftermath that perhaps society will figure out how to make this spill the last one. Though the Gulf disaster leaks as much oil in two days as the entire Bolsa Chica spill, so far it has not killed many beach birds (about 23 at present), mainly because most of the oil has yet to wash ashore or even surface. It’s difficult to gauge how many ocean-foraging birds, dolphins, and whales may have been affected. More than 150 sea turtles have died.

For a look at Bolsa Chica Reserve at its healthy and bird-filled best, see this past article in Living Bird.

When I heard about the massive oil leak gushing up from the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico, it seemed like déjà vu, bringing back haunting memories of an earlier oil spill I witnessed in California two decades ago. A massive oil tanker, the American Trader, carrying millions of gallons of Alaska crude, had ripped a hole in its hull with its anchor as it was being moored in shallow water at an offshore pipeline terminal.

That was in February 1990, and before workers could stanch the flow, more than 400,000 gallons of the thick, black crude had escaped into the water—within sight of one of Southern California’s most sensitive ecosystems, Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve.

I lived just a few miles from Bolsa Chica back then, and it was my favorite place to go birding and photograph wildlife. I knew it would be bad, but nothing could have prepared me for the grim nightmare world I walked through the day after the spill. Vast swaths of the beach sand and rocks were already covered in oil, washed up by the tide, and the whole place reeked of petroleum.

Clean-up crews, clad in yellow plastic rain gear and white hardhats, were already out in force, armed with shovels and rags, trying to mop up the gobs of oil and stuff it into plastic bags. They seemed a portrait in futility. Birds were already dying, washing up on the shore, covered in oil and gasping for air. And flocks of Willets were landing in the goop along the edge of the water to forage. I tried to chase them away again and again, but they kept coming back. I finally went home, sickened by what I had seen.

The next day I went to Terminal Island in Los Angeles Harbor, where a wildlife rehabilitation group had set up an emergency hospital for the birds in a huge metal warehouse. I was a freelance writer and photographer at the time, covering the story for a magazine. And it was a ghastly sight—dozens of stricken birds, including Brown Pelicans (which were then an endangered species), scoters, grebes, gulls, and even a few loons.

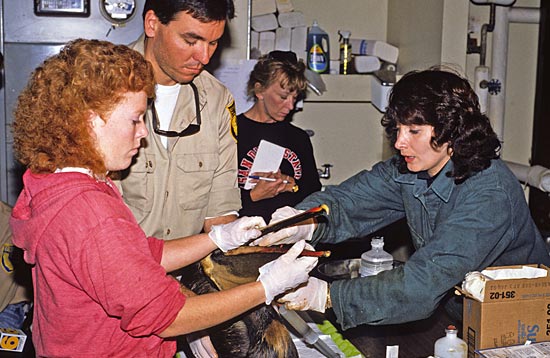

I was deeply moved as I watched the staff and volunteers working with the birds—trying to keep them calm and stabilize their condition. When the birds had recovered sufficiently, each of them washed by hand in hot soapy water until every vestige of oil was gone. This was incredibly labor-intensive, particularly with the pelicans, which required at least three people to clean them—one to hold the bird’s body, one to hold its bill, and one to wash.

I think I was only there for an hour before I set down my camera, donned a raincoat and gloves, and started working with the birds. I’d had a lot of experience over the years handling birds of prey, and I quickly graduated to being one of the bird washers. I ended up working there every day, sometimes for 12 hours or more, until every last oiled bird had been cleaned.

After the birds had been washed and observed for several days, they were released. By that time, they were living in wading pools and freely eating baitfish provided for them. It was a great feeling when we starting taking groups of birds out to be released. Most of them flew away strongly and seemed well. But of course, it was impossible to know for sure what the long-term prognosis would be for each of them after all the trauma they had faced from being immersed in oil. We did band all of them, and very few turned up dead.

As I write, the ultimate effects of the oil leaking from the deep-sea well in the Gulf of Mexico are still a huge question mark. Will they be able to stanch the flow of oil soon, or will it continue to flow for weeks or perhaps months? At this point, no one can say for sure. I dread the thought of those spectacular coastlines and estuaries of the Gulf being fouled by oil. And I dread the dozens—or perhaps hundreds or even thousands—of birds washing up blackened and oily along the ruined beaches.

More on our blog about the oil spill: Bad Place, Bad Timing for an Oil Spill, eBird Gadget Tracks Gulf Coast Sightings.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library