Learn Bird Songs by Listening Deeply: Q&A With Don Kroodsma

By Pat Leonard

April 24, 2017

From the Spring 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Learning to recognize birds by ear may seem daunting, but it’s something Don Kroodsma has been doing for a half-century. We asked the author and birdsong expert to explain how someone can get started with this indispensable birding skill. Kroodsma told us to start by slowing down and taking the time to listen to birds as individuals.

How do we begin to get familiar with bird songs?

Don Kroodsma: The same way we get to know people, I suggest. Suppose you move to a new town and want to figure out who’s who. You get to know one person at a time, starting with a neighbor perhaps, getting to know that one person well enough that you’d rarely, if ever, mistake him or her for another person. Then you “learn” the next person. You wouldn’t start with 100 people gathered in an auditorium and race from one person to the next. I advocate “identifying with” birds instead of just “identifying” birds.

Can you explain what you mean by “identifying with” birds?

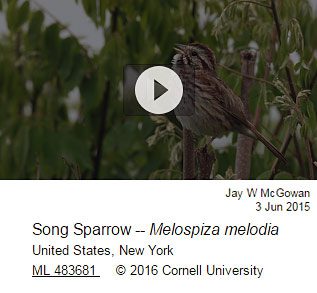

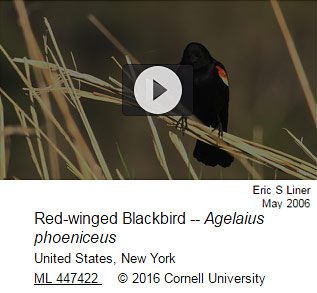

DK: When we try to identify birds we are often creating a list and only the species counts. That’s a critical difference compared with the way I approach birds. For me, I’m listening, so every individual counts because every individual is different; each individual is saying something different and it is enjoyable to listen to in that kind of detail. I would say pick any species that one already knows, like a chickadee or a Song Sparrow. For a Red-winged Blackbird, you could go sit in a marsh and watch individual birds. In the Backyard Birdsong guides (see sidebar) I offer lessons on how to listen to individuals of many species.

What would be an example of listening to individuals?

DK: A Song Sparrow has about eight different songs. Instead of developing some superficial tricks to identify a Song Sparrow, sit and listen to an individual and hear him sing one particular song over and over; eventually, after perhaps 10 to 20 repetitions, he’ll switch to another song. You learn about how an individual bird expresses itself. You do that with a couple of Song Sparrows and you will know Song Sparrows well enough that you never confuse them with another species. As you listen to birds in that kind of detail—what I call “deep listening”—one after one you come to know that species and the variation within it. You come to listen at a different level, one bird at a time, and identifying the “species” comes easy.

Are people who have some musical training or ability better at detailed listening?

DK: Possibly, but I more or less flunked piano lessons as a child, don’t “do” music, and do just fine. I think it’s more important to just have “auditory memory,” an ability to hear a sound and recognize it again, or know that it is different from something else.

How can someone improve their auditory memory?

DK: Recording sounds is one way. I love recording because it’s as if the bird is sitting on your shoulder singing into your ear. Then I love looking at those same songs in spectrograms because I think it’s fairly accurate to say that I hear with my eyes, which are so much better trained than my ears. When I see the song and hear the song simultaneously, the eyes teach the ears how to listen, and vice versa. You can also just use a pen and paper to sketch out what a bird is doing with song—perhaps a long, straight line for a whistle, or short jagged lines for rattles, and so forth. I think we already do this mentally—finding the patterns in the song. Sketching the pattern visually reinforces what the ear hears.

You’ve been studying bird sound for nearly 50 years—what got you started?

DK: During the summer of 1968, former Cornell Lab director Sewell Pettingill taught ornithology at the University of Michigan field station, and he asked me to record some bird sounds for the Lab’s Library of Natural Sounds [now the Macaulay Library]. The rest, as they say, is history! Even after all this time I realize that the more we learn the less we know about bird song. But in the end, I find it immensely satisfying to stand or sit in one place, perhaps with my eyes closed, and hear all that is going on around—to know not only who is who but also a bit of what they’re expressing in song.

More Resources

- More about bird song at DonaldKroodsma.com

- Learn to “see” songs with Bird Song Hero

- All About Birds Building Skills: Songs & Calls

- Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds & Video

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library