Here’s a Scout Week Peek at Our 2014 Big Day Route Through the Southwest

By Hugh Powell April 28, 2014

The team will also look for migrants like Ruby-crowned Kinglets. Photo by Bill Thompson via Birdshare.

The Neotropic Cormorant has recently extended its range into the Sapsuckers' Big Day route.

Big Day starts off near Tucson, with birds like this Magnificent Hummingbird.

The team must reach the Pacific coast by sundown if they are to get birds lke Elegant Terns.

In California's Imperial Valley they'll be on the lookout for Burrowing Owls.

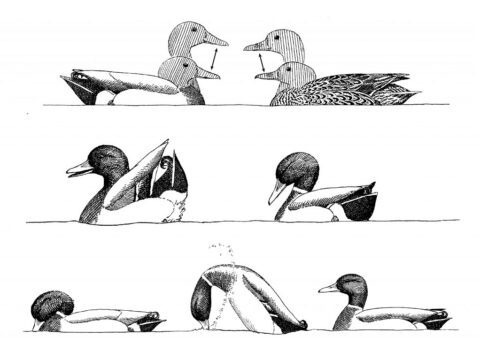

Migrating waterfowl like Bufflehead should be on view in wetlands like the Salton Sea.

By mid-morning the team will be driving across the desert, looking for birds like Black-throated Sparrows.

It’s Scout Week for Team Sapsucker. That’s the name for the frantic week of birding that precedes a Big Day, our biggest conservation fundraiser of the year. And this year, with the Sapsuckers switching venues to a little-explored route in the Southwest, scouting will make all the difference.

Our annual Big Day run has three goals: to raise crucial funds for the Cornell Lab’s conservation work (please donate here); to bring awareness to regional conservation needs; and to see or hear as many birds as humanly possible in a single, sleepless 24 hours. This year’s Big Day is scheduled for May 3. It’s half a continent away from last year’s, and the route is entirely new for the Sapsuckers: a headlong run through southern Arizona and across California to the Pacific Ocean.

The team—consisting of Chris Wood (captain), Jessie Barry, Andrew Farnsworth, Marshall Iliff, Tim Lenz, and Brian Sullivan—have their sights on a species total in the 280 range, and 300 is theoretically possible, they say. But with 450 miles separating the endpoints in Tucson and San Diego, and only about 14 hours of daylight, they’ll need to squeeze every species they can out of every minute they’re birding. That’s why Scout Week is so important.

Last Year Texas; This Year Tucson

The Southwest is a switch from last year’s run in eastern and southern Texas. That Big Day capitalized on epic migration conditions (accurately forecasted by Farnsworth’s BirdCast project) to shatter the North American Big Day record. The Sapsuckers beat the previous record by a full 30 species, racking up 294 species in 24 hours.

So why aren’t they going back to Texas? After three years of Texas Big Days ending with such an exceptional result, the team wanted to highlight a different region. The bird-rich Southwest appealed because it combines high bird diversity with the excitement of Arizona’s specialties in the desert canyons and sky islands of Arizona—birds like Painted Redstart and Red-faced Warbler.

Alongside the great diversity of bird species, there’s a juxtaposition of conservation issues that are familiar to much of the country, including urban sprawl, water usage, and changing habitats and climates. A Big Day run through the region gives the Sapsuckers an opportunity to talk about them.

The Route They’re Calling “El Gigante”

To see a lot of birds, you need to cover a lot of ground—and this route is demanding. It spans chilly mountain pine forests, baking desert flats, quiet river canyons, and wave-tossed seacoast. Even the date of the Big Day involves a strategic compromise: early enough in the year to catch ducks and shorebirds in California; late enough to find migrants moving up the Rocky Mountain chain; and timed for a weekend to avoid the worst of the Southern California traffic. Here’s how it should play out:

In Tucson’s predawn darkness the team will listen for owls, nightjars, and the occasional migrant songbird passing overhead. When dawn hits they’ll scour Arizona’s deserts and mountain forests trying to get their list into the triple digits before most people will have had a decent breakfast. They’ll need to leave Tucson by about 8:45 to stay on schedule.

From there they’ll drive through the bleak Mojave Desert, scanning the skies for Swainson’s Hawks and Prairie Falcons. By midday, they’ll be at either the Salton Sea, a famously salty, stinky wetland near the Mexican border, or in small wetlands around Yuma, Arizona. (It depends on what they find during Scout Week.) They’ll be searching out throngs of ducks, shorebirds, and gulls stopping over in precious wetlands during their migration. After less than an hour on their feet, they’ll head onward to spend perhaps 15 minutes of birding on a dash through the Cuyamaca Mountains. They’ll hope for specialties like Lawrence’s Goldfinch and Mountain Quail.

Then comes the biggest logistical wild card of the day: how to get across San Diego, avoiding the Padres’ game-day traffic, to wind up on the coast with enough light to get Elegant Terns, Brant, Surfbirds, and the like. Once the sun goes down they’ll be looking for roosting shorebirds, tracking down geese lingering at city parks, and having a second listen for any owls they missed the night before.

That rushed Tucson morning could come to seem like the day’s most luxurious hours of birding. After Arizona, the team will spend less than an hour at any other site.

A Bird List That Highlights Conservation Issues

The route through the Southwest includes amazing scenery and stunning birds, but it also includes lands with serious conservation concerns. Much of the country shares these concerns, but here they are thrown in stark relief. By connecting birds and habitats to conservation issues, we’re hoping to raise the public profile of conservation in Arizona, California, and beyond.

Urban sprawl. Just the fact that the Sapsuckers need to plan their itinerary around traffic is an indication of the problem of urban sprawl. Though traffic jams are an annoyance of modern life, the tangles of highways and development that cause it also mean that there’s less natural habitat available. The threatened California Gnatcatcher has the misfortune of using the same kind of dry, sunny coastal hillsides that humans have flocked to in the last century. California Gnatcatcher will be a key species for the Sapsuckers as they near the end of their day.

Water use. The Willow Flycatcher is one bird the Sapsuckers most likely won’t get, partly because of water use issues that also affect humans in the region. Willow Flycatchers that nest in the Northwest won’t come through until the second week of May. The local nesters (an endangered subspecies known as the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher) are so rare that there’s essentially no chance of catching an early arriver. These small, brownish flycatchers nest along flowing streams and have declined to only a few thousand individuals. A century ago they were much more common, but pressures such as drought, diversion, channelization, development, and dam construction, as well as historical grazing practices, have nearly wiped them out of stream corridors in the Southwest.

Land use. The team will be birding across many Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service lands, where decisions about logging, burning, and grazing regimes greatly influence habitat characteristics. In reports like the State of the Birds 2011 report, data from our eBird project has been used to determine how well individual species, such as Lucy’s Warbler and LeConte’s Thrasher, are represented on different types of land, helping agencies zero in on specific needs that they can plan for.

Changing climate. Abnormally warm and dry weather in recent years has wrought large changes over the Southwest, including outbreaks of bark beetles and more frequent, more severe, or larger forest fires. The team will hope to find White-headed Woodpecker in the Cuyamaca Mountains, but this species is scarce here, where it relies mainly on live, old-growth Jeffrey pines and may be harder to find.

Of course, along with habitat change comes the possibility of new birds taking advantage of the shift. In the past couple of decades a small number of primarily Mexican species have started expanding into the Southwest. Some former rarities are now regular enough for the Sapsuckers to factor them into their route planning, such as Neotropic Cormorant and Rufous-capped Warbler in Arizona, and Reddish Egret and Yellow-crowned Night-Heron in California.

The Sapsuckers have their work cut out for them. They’re in Arizona and California right now, along with a band of colleagues, friends, and locals who are helping them find the route’s best birding spots. When Friday, May 2, ticks over to Saturday, May 3, they’ll put hands to ears to begin listening for owls—and start connecting the dots on their scout map, bird by bird. Follow their progress on Facebook, and please donate to our cause to help them on their way.

Read more coverage of Big Day from previous years:

- 294 Species and One Shattered Record on “Almost Perfect” Big Day

- What’s It Like to Find 264 Species in One Big Day?INVALID VIDEO SHORTCODE

- 264: A New North American Big Day Birding Record

- Birds Win in World Series of Birding

(Images at top via Birdshare: Magnificent Hummingbird by Mauro Roman, Ruby-crowned Kinglet by Bill Thompson, Black-throated Sparrow by Larry Selman, Burrowing Owl by Todd Steckel, Bufflehead by Corey Hayes, Neotropic Cormorant by David Quanrud, Elegant Tern by Mike Forsman.)

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library