For Tropical Bird, Violin More Resonant Than Aria

November 13, 2009

Birders visiting the New World tropics rarely have to wait too long before hearing male manakins at their leks. With a bit of careful creeping through the undergrowth, you’ll often find a bizarre gathering of the little fist-sized birds hopping, strutting, or sidling along their perches in the hopes of attracting a mate.

The soundtrack is no less weird: each species has a characteristic pop, snap, ruffle, or whir typically produced mechanically with their wings. No vocal cords required. (You can listen to a selection by searching the Macaulay Library for “manakin.”)

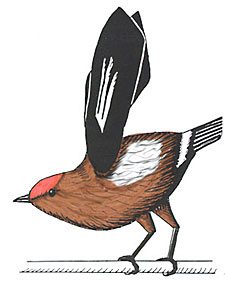

One species, the Club-winged Manakin of Ecuador and Colombia, makes a thin violin-like whistle by knocking its wings together behind its back. This bird is near to the heart of Kim Bostwick, curator of the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates. In 2005 she used high-speed video to reveal how the bird does it: by rubbing a stiffened wing-feather tip across seven remarkably precise ridges set into the thickened shaft of the adjacent feather. (It’s this feather that gives the bird its common name.)

Now, in a paper just out this week, Bostwick and colleagues have found two unusual ways the manakin’s wings modify that feather-scraping-on-ridges sound. First, that thickened feather shaft picks up the vibrations and begins to resonate, making the sound louder much the way a violin’s body amplifies the sound of a bow against strings. Next, the researchers looked at other feathers up and down the bird’s wing. Using lasers to watch the feathers vibrate, they saw that even these “normal” feathers picked up the sound. They began to vibrate in phase, adding some harmonic effects to the sound and possibly making it louder still. That short, reedy sound you heard in the video is the complicated result of an entire wing (or two) working together.

Fascinatingly, they conducted the same test with close relatives—other manakins that don’t make wing sounds. Those feathers also tended to vibrate at 1500 Hertz, though much more weakly and not in phase with each other. That result hints at how evolution could have yielded the Club-winged Manakin’s sound, using as raw material an inherent quality of manakin feathers and slowly modifying it.

But what makes evolution head off in such oddball directions? It’s thought that manakins court acrobatically rather than vocally because of sexual selection, a branch of natural selection. Although playing the world’s smallest violin behind its back doesn’t help a male Club-winged Manakin find food or fend off predators, it does attract mates—so birds that are better at it pass on that ability to future generations. What’s neat about this process is that it puts females in a powerful position. So-called choosy females, by selecting certain abilities in males and ignoring others, actually drive the evolution of their species as much as external events do—even to the point of producing outlandish thickened feathers that work like a musical instrument.

Bostwick and her colleagues note that this kind of sound production is basically unknown among vertebrates. Plenty of insects do something similar called stridulation. The peaceful chirping of crickets on a summer night, for example, comes from hundreds of cricket legs rubbing against hundreds of hard cricket exoskeletons, amplified by resonating throughout their little cricket bodies. But among the vertebrates their only peer known so far is the Club-winged Manakin. As Bostwick and colleagues put it:

“The mechanism employed by male Club-wing Manakins crosses taxonomic boundaries and places these birds squarely among more arthropod-typical mechanisms of sound production…. The presence of these extremely rare traits in a bird highlights an arthropod-vertebrate convergence enacted by choosy females, with the structural features of the modified secondary feathers appearing to have been exaggerated from resonant characteristics that probably existed in the ancestral feathers.”

Of course, none of this answers the question of why the males don’t simply open their beaks, whistle an F-sharp, and have done with it. While they were at it, they could probably throw in some slides, a trill, or a crescendo, like a “normal” songbird. Except that apparently female Club-winged Manakins just don’t find that version of the sound attractive. And as any rock star, stand-up comedian, tap-dancer, skateboarder, footballer, or husband can tell you, that’s the whole point.

Read more about Bostwick’s research in this 2005 BirdScope article and in this post by Carl Zimmer at Discover magazine’s blog. If you’ve never seen a manakin moonwalking, this clip from Nature is a must-see.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library