First-Ever World Shorebirds Day Highlights Need for Conservation

By Pat Leonard September 5, 2014

One of the most beautiful experiences in nature may be the sight and sound of thousands or even millions of shorebirds bursting into flight, dipping and wheeling as a coordinated unit, not once colliding with each other. But with worldwide shorebird populations declining across the board, it may be a spectacle future generations get to witness all too rarely.

To celebrate the amazing migrations of shorebirds, and to raise awareness of the challenges they face, the first ever World Shorebirds Day is taking place on September 6, 2014. Participants are being asked to count shorebirds, either on their own, at scheduled events, or at specific shorebird hotspots—and to report their counts through eBird.

The majority of shorebird species can be found near shallow water and include plovers, sandpipers, stilts, avocets, oystercatchers, shanks, snipes, and woodcocks.

“It’s that group of birds which are largely found next to the shore, whether it’s beach shores or inland wetland shores, but they do occur in other habitats as well,” says Rob Clay, director of the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. “Some species are grassland dependent, others are forest dependent; there are even a few species that occur in arid habitats. They may be found on the coast or at 4,000-plus meters up in the Andes.”

And they are clearly in trouble. Half the species that regularly occur in the United States and Canada are either highly endangered or of special concern, according to the U.S. and Canadian Shorebird Conservation Plans. In South America, of 34 breeding species, 32% have been identified as highly endangered or as a species of high concern, according to Clay. The new 2014 State of the Birds Report, being released September 9, includes a call for international efforts to halt the steep decline in shorebird populations. What’s happening in the Western Hemisphere is magnified in the Eastern Hemisphere where pollution and development-fueled habitat loss have put species such as the Spoon-billed Sandpiper on the brink of extinction. The odds have been stacked against shorebirds for a long time.

“As a group they tend to have small global populations compared to a lot of other species,” says Ken Rosenberg in the Cornell Lab’s conservation science department. “Some of them number in just the tens of thousands instead of millions.”

Those low numbers reflect a legacy of hunting in the last century from which some populations have never recovered. The Eskimo Curlew was hunted to extinction. Shorebird hunting in the Caribbean and northern South America continues today and this is where some of the steepest population declines are occurring.

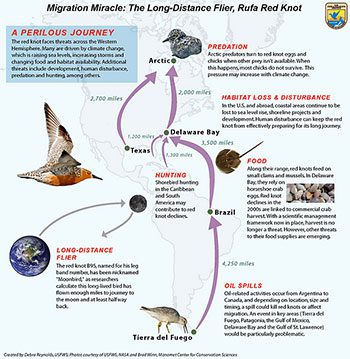

Another reason for shorebird vulnerability stems from their spectacular long-distance migrations—some species travel from one end of the world to the other, from breeding grounds in the high Arctic to wintering grounds in Patagonia or New Zealand. They flock together at key stopping points along the way. Red Knots epitomize the vulnerability this behavior presents.

“Almost the entire eastern North America population of Red Knots stops in Delaware Bay for one week during migration,” Rosenberg says. There, the knots have historically fueled up on horseshoe crab eggs—a food source that has crashed from overfishing. “If they don’t get enough food at that spot they literally can’t make it up to their Arctic breeding grounds and that entire population can’t breed. They’re highly vulnerable because of these bottlenecks at migration stopover points where they congregate. ”

That’s why the shorebird reserve network has adopted a conservation strategy that focuses specifically on these critical stopover points. While flocking to these sites makes some shorebirds more vulnerable to population declines, Rob Clay says that same behavior can be a positive for conservation.

“If you can safeguard the critical network of sites that the birds need,” Clay says, “then you can essentially ensure the maintenance or restoration of their populations.”

The Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network currently includes 89 sites in 13 countries, though Clay says there are probably 400 to 500 key sites throughout the Western Hemisphere. Becoming part of the network includes a voluntary commitment from landowners to take the needs of shorebirds into consideration in their management of the sites.

Restoring shorebird populations benefits humans as well, because it may preserve wetlands that act as a buffer during extreme weather, which is predicted to become more commonplace because of climate change. After an earthquake and tsunami devastated the area of Concepción, Chile, a few years ago, Clay notes that the communities least impacted were located behind the one small coastal wetland that remained in the area.

“That really underlined the value of coastal wetlands as a buffer,” says Clay. “Up until that point, the wetland had been slated for development. Those plans were stopped and the area is now, hopefully, about to become a protected area.”

Though the challenges may seem overwhelming, individuals do have a role to play in conserving shorebirds simply by reporting them to eBird.

“That’s actually one of the simplest ways that anybody who is interested in shorebirds can help,” notes Clay. “Just reporting observations through eBird enables us to build up a much better understanding of where the shorebirds are and when and what types of habitat they’re using. The house is not entirely burned down as yet but there’s a pretty significant fire raging through it. And the time to act is now before it is too late.”

What’s it like to study shorebirds?

This video takes you to the Alaskan tundra for a day-in-the-life of a shorebird researcher.

For more information on shorebirds:

- World Shorebirds Day official website

- Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network

- Tracking Alaska’s Godwits, a 20-minute video about the Bar-tailed Godwit’s 8-day nonstop migration to New Zealand

- Flight of the Kuaka, a Living Bird article about Bar-tailed Godwit migration.

- Louisiana report: Wilson’s Plovers and why we monitor them (slideshow)

- Sandpiper or plover? Or both? A field report from Chile [Video]

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library