Beginnings: A Young Birder Tells Us How She Got Started

Text and images by Rachael Butek December 19, 2011

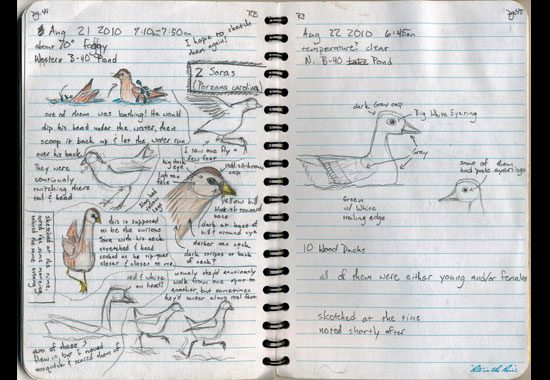

Rachael Butek's amazing field notes helped her win the ABA's Young Birder of the Year award in 2010.

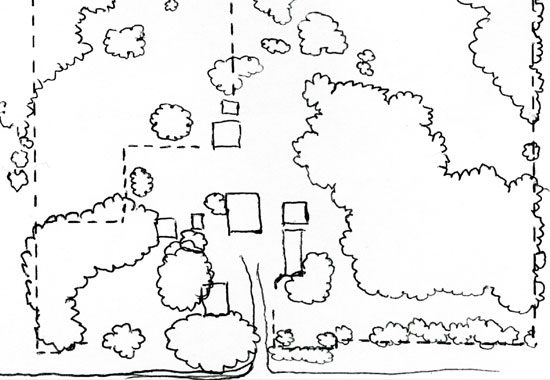

Rachael's hand-drawn map of her family's Wisconsin farm.

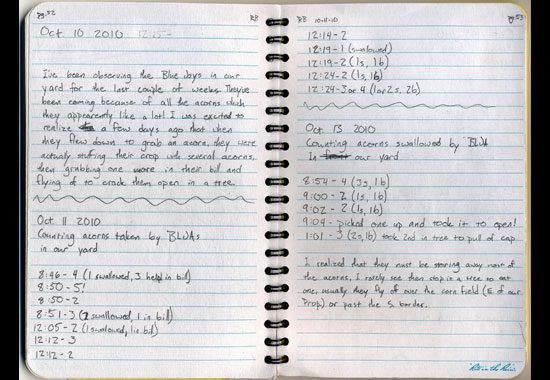

Rachael also kept detailed watch as Blue Jays gathered acorns in the fall.

Keep reading to learn about how Rachael was inspired by a Song Sparrow.

All through our lives we draw inspiration from our elders, but there comes a point when we can turn around and start drawing inspiration from the young people coming up behind us. At a recent meeting of the Ohio Young Birders Club, we had a chance to hear from Rachael Butek, a recent high-school graduate who combines great birding skills with keen powers of observation and interest in the world around her.

Rachael gave the keynote address at the meeting and shared her story of how she got started, the pioneering bird watcher who gave her inspiration, and her pursuit of the American Birding Assocation‘s Young Birder of the Year award. We found her presentation so enjoyable and inspiring that we asked her to retell it on our blog. –Hugh Powell

I first got interested in birds when I was 16, all because of a sparrow in my Wisconsin backyard.

It was just a “little brown bird” at first sight, but when I took a closer through my grandparents’ binoculars, I saw it was a delightful blend of buff and chestnut and stripes. And that was about all it took—just one simple little bird to change my life.

I pulled out our Golden Guide and was nearly scared off by how many different kinds there were. But I was determined, so I started narrowing down my possibilities. The nifty little range maps helped narrow down the species considerably. Then I noticed that the sparrows divided neatly into two groups, the birds with stripes on their breast, and the ones without.

From there I started reading descriptions, checking off birds one at a time. Mine didn’t have any yellow by his eye, and he had too long of a tail to be another one. He didn’t seem to have a buffy collar, and he definitely didn’t have that eyering either. Eventually, the only one left was the Song Sparrow.

That was my first real bird identification, and I have to say, I was pretty proud of myself! Ever since then I have loved Song Sparrows, and sparrows as a whole have become one of my favorite families of birds.

From sparrows to warblers to tanagers

I didn’t realize it then, but I was already hooked. I kept a list of feeder birds all winter long, and six months later I knew them well enough to start noticing migrants. When I saw my first American Redstart in real life, after months of seeing them in my field guide, I was astonished to realize they actually lived in Wisconsin! A little yellow bird in our plum trees stumped me until I noticed his rufous cheek patch—which immediately gave him away as a Cape May Warbler.

Then, one day a brilliant yellow bird with an orange head landed on our feeder pole. I was so astonished I could hardly call my family or reach for the camera. It was a Western Tanager, a rare bird in Wisconsin. I reported it to eBird—I don’t recall exactly what I said, but I’m pretty sure it was something classic like, “It looked just like the picture in the book!” When it came to taking field notes, I had a looong way to go yet.

Lessons in watching, from one of the best ever

By early summer I was thoroughly infatuated with birds. Soon I became fascinated with Margaret Morse Nice. This woman, born in 1883, became a busy wife and mother but still found enough time to study Song Sparrows in her yard in Columbus, Ohio, for eight years. Her studies were so groundbreaking that Ernst Mayr (one of the most prominent biologists of the twentieth century), said, “She almost single-handedly initiated a new era in American ornithology.”

I was captivated by this, so I got “The Watcher at the Nest,” her story of studying these birds. I fell in love with her detailed observations and her style of note taking. She described things in such detail, yet simply enough to make perfect sense.

That year I decided to compete in the American Birding Association’s ‘Young Birder of the Year‘ contest. My focus was on note-taking and, inspired by Margaret Morse Nice, I knew I shouldn’t have to go far from my backyard to find good note-taking material. Sure enough, our 10-acre hobby farm easily provided me with a summer’s worth of mini-research projects.

A summer of study

I began by taking a census of the birds breeding on our property. Each day of the week I counted different groups of birds. For instance, Thursday was sparrow and bunting day. I would set out early in the morning and start counting the half-dozen different species in that “group,” keeping notes on where I saw or heard individual birds. By counting almost every day for a few weeks, I was able to get a good idea of the overall population of birds breeding on our property.

Later that summer, a massive rain storm flooded about half our acreage and brought in a whole new array of wildlife. So, I started my “pond project,” spending the next month and a half exploring this interesting change in my little ecosystem. I investigated everything from snails to sandpipers, highlighted by a pair of Soras that let me watch and sketch them for an entire morning.

Next came Blue Jays. I realized they were swallowing acorns whole and then flying off with them, presumably to store them for the winter. I wondered just how many acorns a Blue Jay could hold in its crop, so I started watching and counting. After a couple of days, I concluded that they normally took two or three at a time, but the occasional greedy jay took as many as five at once!

Young Birder of the Year

After one of my most wonderful summers ever, I packed up all my entries and shipped them off to the ABA. All winter long I continued taking notes, painting, and taking photos. I kept track of my favorite Northern Shrike as she terrorized the feeder birds, and I followed the regrowth of the tail on one of our cardinals, who showed up at our feeders without his tail.

One fine spring day, I was astonished and delighted to hear I had been named the 2010 Young Birder of the Year. Among the great opportunities that came from this, I especially treasured getting an invitation to visit, and then join, the banding crew at nearby Beaver Creek Reserve. They are now kindly training me in MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) bird-banding methods. Ever since learning about Margaret Morse Nice and her studies on Song Sparrows, researching birds has been a passion with me. What better way to get started than by banding them?

Birding has radically changed the way I see the world. As I look forward to college, I’ll remember Margaret Morse Nice’s suggestion to look closely at things and to consider what they mean. When she began watching Song Sparrows, she recalled, “I went to the books and read that this species has two notes beside the song, and that incubation lasted ten to fourteen days and was performed by both sexes; meager enough information and all of it wrong.”

Hopefully, as I further my education in the natural world, I’ll be able to learn some new things myself, and make a difference to the birds in my own backyard.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library