A Live Visit to the Snowy Owl Nest on Our Live Cam

By Pat Leonard July 24, 2014

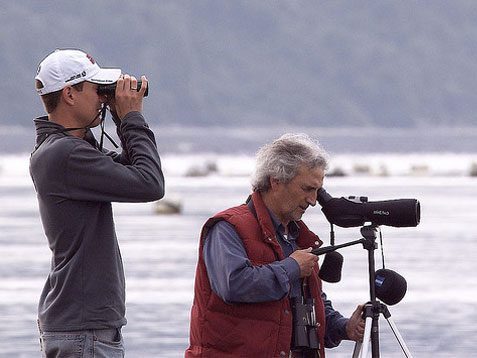

Every three days this summer, Denver Holt of the Owl Research Institute tries to check each of the 20 Snowy Owl nests he’s monitoring. [Read about a previous nest check.] Today, our goal was to find the two surviving Snowy Owl chicks from our Bird Cams project nest to see if they are still alive and how they are doing. Holt has brought along Cindy Shake of UMIAQ, an organization that provides support for Holt’s research, as another helpful set of eyes. We strike out across the soggy tundra in the vicinity of the live camera to see if we can spot the little ones.

With a light mist blowing on the ever-present wind and the glowering low-slung cloud cover it seems impossible to locate anything small and gray at a distance. The Snowy Owl parents are nearby and they see everything with their super-powered eyesight. They are paying close attention to us, so there may be a chick nearby. As usual, with 23 years of experience under his belt, Holt spies a chick first. It’s hunkered down near a hummock where one of the adults has left a lemming. The chick sees us coming.

Shake and I hang back while Holt moves closer. While he’s concentrating on the chick, Mom swoops by to snatch the lemming for safekeeping. Dad’s remaining a bit passive, something Holt has noted in the past. He expresses nothing but admiration, though, for the female and the job she has been doing. “She’s magnificent!” he declares.

Holt snags the owlet and takes a closer look. Who do we have here? This is chick number 788, according to the last three digits on the leg band Holt put on weeks ago. The owlet’s primaries are growing in nicely and it seems to be the proper size for its age. This chick is 34 days old as of today (July 22) and walked off the nest a couple of weeks ago. This is the younger of the two chicks we hoped to find. Sibling number 787 was the first chick to hatch and the first to leave the nest, just a couple of days before this one.

Holt looks over the bird in his hand and feels confident that this chick is a female. Its dark ashy color is one clue but he also looks at the number four secondary feather. “If it shows spots that don’t reach all the way to the rachis—the shaft of the feather—then it’s a male,” Holt explains. “If the feather shows bars that do reach all the way to the shaft, which is the case with this one, then it’s a female.”

Holt has tested the accuracy of this method by cross-checking field observations with later DNA analysis. The score: 140 correct matches out of 140 chicks whose gender was determined in the field using the feather method. Holt coauthored a paper on these results in the Journal of Raptor Research in 2011.

After a quick visual check, Holt sets the bill-clacking owlet free and she does her hobble-hop away with, I imagine, something akin to relief, if an owl can feel such a thing. After she’s put some distance between us, Mom returns with the lemming and feeds her—a good thing to see. Beautiful number 788 still has another two to three weeks to totter about the tundra before she can take her first awkward flights. Fledging usually takes place when chicks are 45 to 55 days old. Though we’re happy to have found 788, the overall mortality among this year’s chicks is pretty sobering—about 70% by Holt’s reckoning, though it’s not clear why.

We spend another 15 minutes or so looking in vain for chick number 787. The parents seemed to lose interest in us too, so perhaps we were never even close. However, when we returned home we learned to our relief that several people watching the Bird Cams, including project assistant Hollie Sutherland, had seen the owlet scurry away as we approached.

In the end, we abandon the search so as not to stress the adults any more than necessary because while we are on the scene, they have to be on alert. The goal, as always, is to balance the need for scientific study with the overall wellbeing of the birds being studied. And no one wants to end up on the business end of those razor-sharp claws!

For more about Snowy Owls, check out:

- Banding Snowy Owl Chicks With Researcher Denver Holt

- A Season of Snowy Owls, in the Spring 2014 Living Bird magazine.

- Project SNOWstorm Seizes the Moment to Take a Closer Look at Snowy Owls

- A Snowy Owl Sequel?, January 2015 blog post

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library