On Safari in the Okavango Delta of Botswana

By Gary Kramer January 15, 2009

Not far from camp we come upon a herd of Cape buffalo in the tall grass. Just beyond, a giraffe stops to make sure we pose no threat, then continues stripping leaves from an acacia tree. As we leave the savanna and move toward an expanse of water and reeds, our guide points out a band of red lechwe antelope. We move closer and the herd bolts, racing off across the shallows in a burst of spray. Less than 100 yards away stands a brilliantly hued Saddle-billed Stork, searching the shallows for prey, and along a grassy bank, we spot a pair of endangered Wattled Cranes. This was just our first 30 minutes of a game-viewing and birding safari in the Okavango Delta of Botswana, a vast area teeming with wildlife.

In contrast with much of a changing Africa, Botswana is still safari country—a place where visitors can still find a classic African experience. It is a land of vast unpeopled savannas, great forests and grassy plains, and clear rivers that wind among palm-fringed islands to vanish in the Kalahari sands. Independent for more than 25 years, Botswana is nearly the size of Texas, but it has a population of just over a million people. It is notably safe and stable and blessed with an invigorating climate and a growing economy. Wilderness, immense in size and rich in wildlife, covers thousands of square miles, and nearly a quarter of the country is devoted to huge wildlife reserves. Here are mammals and birds in variety and abundance. Botswana is truly a stronghold of the old Africa.

For sheer beauty, vast herds of game, and wildlife diversity (including more than 600 species of birds), the Okavango Delta has no peer. The Delta is a miraculous oasis of islands, shallow marshes, floodplains, and meandering channels. Its life blood is the Okavango River, which rises in the Angolan Highlands and flows 650 miles to Botswana, fanning out to create a 7,000-square-mile oasis.

Last July, I arranged my twenty-seventh trip to Africa and my sixth to Botswana. It was a 13-day adventure for 10 people to the Okavango Delta and Chobe National Park. After a 17-hour trans-Atlantic flight from New York, we were ready for a shower and an overnight stay in Johannesburg.

The next morning we boarded a flight to Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. We stopped there not only to see the falls—known as the “Smoke that Thunders”—but to spend a day birding in the unique rainforest that surrounds it. The veil of mist rising from the chasm of the falls supports a microclimate that is alive with birds. Well-worn footpaths lead to the falls. Less than a five-minute walk from the entrance, we saw a pair of Trumpeter Hornbills flying over the falls. Before long we ran into a flock of Helmeted Guineafowl in the underbrush and spotted Blue-breasted Cordonbleus, Red-billed Firefinches, and Common Bulbuls foraging along the paths. Collared and Scarlet-crested sunbirds, long-tailed African Paradise-Flycatchers, and Green Woodhoopoes are among the most colorful and interesting birds found there. The most common mammals are the shy Chobe bushbuck and the conspicuous Chacma baboon.

The next day we left Victoria Falls and traveled to the airport at Kasane in Botswana. At Kasane we boarded our chartered Cessna Caravan and flew for 75 minutes to reach Eagle Island, our first camp in the Okavango Delta. The pilot stayed low so we could view the countryside, and the flight passed quickly. At first we flew over mostly dry savanna with a few scattered trees, but about 40 minutes into the journey green patches of vegetation and narrow waterways began to appear. By the time we landed on the dirt airstrip at Eagle Island, we were deep in the Delta and surrounded by a landscape dominated by islands, wetlands, and riparian habitats.

Eagle Island at Xaxaba Lagoon is typical of several small but luxurious safari camps found in the Delta. The camp has 12 thatched-roof tents built on teak platforms. Amenities include air conditioning and heating, flush toilets, hot showers, and daily laundry service. The gourmet meals are served with fine South African wines, and a nightly campfire adds to the safari atmosphere. Eagle Island is surrounded by water, and all game viewing and birding is by boat—either a powerboat or a canoelike mokoro, which is poled through the swamps. Guided walks on the larger islands are available as well.

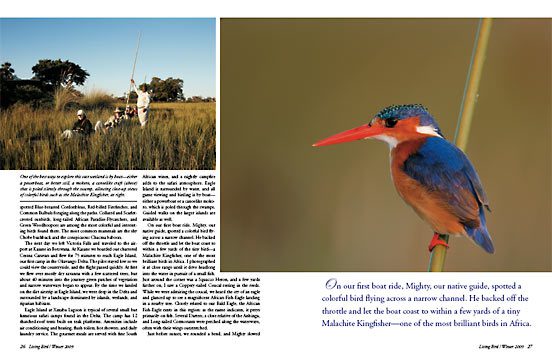

On our first boat ride, Mighty, our native guide, spotted a colorful bird flying across a narrow channel. He backed off the throttle and let the boat coast to within a few yards of the tiny bird—a Malachite Kingfisher, one of the most brilliant birds in Africa. I photographed it at close range until it dove headlong into the water in pursuit of a small fish. Just around the corner was a Squacco Heron, and a few yards farther on, I saw a Coppery-tailed Coucal resting in the reeds. While we were admiring the coucal, we heard the cry of an eagle and glanced up to see a magnificent African Fish-Eagle landing in a nearby tree. Closely related to our Bald Eagle, the African Fish-Eagle nests in this region; as the name indicates, it preys primarily on fish. Several Darters, a close relative of the Anhinga, and Long-tailed Cormorants were perched along the waterways, often with their wings outstretched.

Just before sunset, we rounded a bend, and Mighty slowed down, pointing ahead to a large pod of hippos blocking our path. The huge animals were curious and actually moved toward the boat. After taking a number of pictures with a telephoto lens, we backed away and found another channel around the hippos. On the way back to the camp, we spotted several Nile crocodiles basking on the river banks and added African Pygmy-Goose, Red-billed Duck, Winding Cisticola, African Green-Pigeon, and the secretive Black Crake to our growing bird list.

Each day after lunch, we had time to rest before our afternoon boat ride. On the early morning excursions, a light jacket was mandatory, but by afternoon the sun warmed the air to the mid-70s Fahrenheit, and a light breeze materialized just in time for a siesta. A gentle wake-up call and afternoon tea fortified us for the final boat ride of the day.

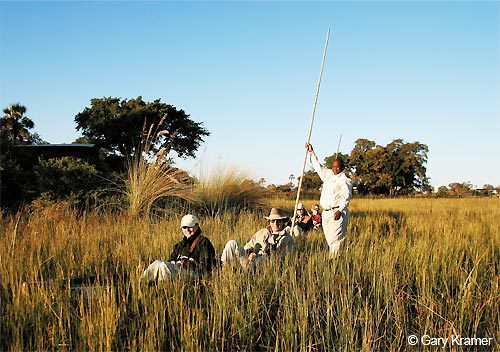

An interesting way to explore the wetlands of the Delta is by mokoro. These used to be handmade wooden boats, but to preserve the large riverine trees that were formerly used to make them, they have been replaced by fiberglass canoes. Each mokoro can accommodate two passengers, and a guide poles the boat through the shallow water and reed beds. During our mokoro excursions, we spotted Pied Kingfishers hovering over the wetlands, Great Egrets and Spur-winged Geese foraging in the shallows, and African Marsh-Harriers on the wing, searching for prey.

After a few days at Eagle Island Camp, we transferred by light aircraft to Khwai River Lodge on the edge of the Moremi Wildlife Reserve. Here the game viewing was from safari vehicles. The accommodations were just as superb as those at Eagle Island.

Every morning we were awakened at sunrise by the cackle of Red-billed Francolins just outside the door. At breakfast we planned the game drives. We saw the more common mammals (impala, zebra, wildebeest, and warthog) and birds (Ring-necked Turtle Dove, Red-billed Francolin, Burchell’s Glossy-Starling, and Grey-headed Sparrow) on most drives, and the challenge became finding and photographing the more elusive species. Every drive brought its delights—the spiral-horned greater kudu we nearly missed in the brush only yards from the Land Cruiser, a flock of noisy White-faced Whistling-Ducks feeding in a papyrus marsh, a black-maned lion feeding on a zebra kill, a stately Wattled Crane with its characteristic red wattles searching the grasslands for a snack.

Possibly the best way to explore the Okavango is via the silent, canoelike mokoro.

Author Gary Kramer spotted these two Wattled Cranes in his first 30 minutes in Botswana's famed Okavango Delta.

The tiny Malachite Kingfisher is one of the most brilliant birds in Africa.

For a flock of oxpeckers, a hippo basking in the sun is one giant dinner table laden with ticks.

Helmeted Guineafowl visit a waterhole.

Violet-eared Waxbills stop off at the fountain on the grounds of the Savute Elephant Camp.

The Okavango stretches away beneath dark clouds.

Some of the best birding was along the Khawi River, where terrestrial birds came to drink and forage and wetland species spent most of their time. Near camp, a Blacksmith Plover scolded us with its klink, klink, klink—a call that has been likened to a blacksmith hammering on an anvil and is the origin of the species’ common name. We spotted a Common Moorhen, one of the few birds found in both North America and Africa, a pair of African Jacanas walking on the lily pads, and a brilliant Little Bee-eater catching insects. Helmeted Guineafowl and both Burchell’s and Double-banded sandgrouse came to drink. Also near the water we saw Long-toed Lapwings, White-faced Whistling-Ducks, Egyptian Geese, Great White Pelicans, Hadada Ibis with their raucous calls, the odd-looking Hamerkop, the huge Goliath Heron, and the African Spoonbill.

One of our most interesting encounters was watching Yellow-billed and Red-billed oxpeckers foraging on hippos as they lay out of the water resting. Oxpeckers and hippos have a symbiotic relationship—the hippos provide a food source for the birds while the oxpeckers keep the hippos free of ticks and other parasites—but the oxpeckers were annoying the hippos. We watched as these huge animals stood up to shake off the oxpeckers or abruptly ran into the water to evict the birds. These maneuvers rarely succeeded for long; the oxpeckers landed again and resumed their foraging antics on the heads or backs of the partially submerged hippos.

The final stop was Savute Elephant Camp in Chobe National Park. Every animal and bird is spectacular in its own right, but elephants are the creatures of the African landscape that inspire the most awe. By virtue of their size alone they command respect. Botswana is one of the last strongholds of the African elephant, with a population estimated at 60,000 animals.

In front of Savute Elephant Camp, an artificial waterhole attracts a nearly constant procession of elephants and other mammals as well as birds. Bird watching was an armchair endeavor, with Red-billed and Swainson’s francolins, Helmeted Guineafowl, and Grey Go-away birds coming to the waterhole to drink. A fountain in camp provided close-up views of Meyer’s Parrots, Violet-eared Waxbills, White- browed Sparrow-Weavers, Southern Yellow-billed Hornbills, and others.

The game drives produced an array of mammals, including the only cheetah we saw on the trip, two leopards, a pride of lions, giraffes, and a variety of antelope species. The dry savanna at Chobe National Park allowed us to add several species to our growing wildlife list and to see some birds in greater numbers. Included were Tawny Eagles, Bateleurs, Ostriches, Long-tailed Shrikes, magnificent Kori Bustards (Africa’s heaviest flying bird), a pair of Giant Eagle-Owls, White-backed Vultures, Namaqua Doves, Bradfield’s Hornbills, and Southern Ground-Hornbills.

A favorite bird of almost everyone was the Lilac-breasted Roller. Abundant in the dryer regions of southern Africa, it is a large, colorful fly-catching species. On two different occasions, we watched as a roller caught grasshoppers only a few yards from our Land Rover.

By the time the trip was over our group had tallied more than 150 species of birds and dozens of mammals. The last afternoon we stopped just before sunset, and our guide, Leopard, set up a small table with drinks and snacks. The customary sundowner, a refreshment break beneath a fiery African sunset, was a fitting end to a great trip. Knowing that our trip was coming to a close, our group reflected on the past 13 days, and we all vowed someday to return to Botswana. I know that I will.

Gary Kramer is a freelance writer and photographer based in California. He offers escorted trips to Botswana, Kenya, and Tanzania. Visit his web site at www.garykramer.net or call (530) 934-3873.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library