Where Did All Those Canada Geese in Town Come From?

By Pat Leonard September 17, 2013

Even if you’re not a bird watcher, chances are you know what Canada Geese look like. Love them or hate them, there sure are a lot of them—in parks, on golf courses, maybe even your backyard. It’s hard to believe there was a time when these birds were on the brink of being wiped out in North America. Now, they’re overrunning our city parks, golf courses, and farm fields, crowding our national wildlife refuges, and causing hazards at airports. There are even concerns about public health and water quality from all those goose droppings.

Canada Geese are a native species whose recent population explosion is thanks to human effects on the landscape. So what can or should be done about them? We checked in with Cornell Lab conservation scientist Ken Rosenberg and Paul Curtis, who coordinates Cornell’s Wildlife Damage Management program. They described the differences between migratory and resident Canada Geese, the problems that can arise from high goose populations, and a range of approaches for approaching Canada Goose problems.

How Many?

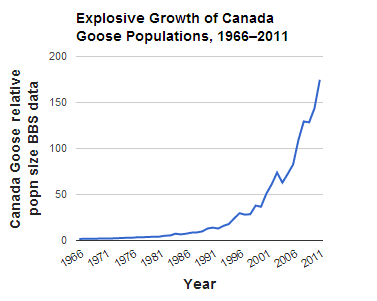

According to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013 report [PDF], there are more than 5 million breeding Canada Geese in North America. But within that vast number are two distinct populations: migratory birds that breed in northern North America and winter in central and southern North America; and resident birds that live in and around towns year-round. Both migratory and resident numbers have increased, but most of the trouble has come from resident birds.

Most Canada Geese used to be migratory—those big vees of “honkers” that signal the change in seasons each year as they pass overhead. Though there are still several million migratory Canada Geese, for a period at the end of the nineteenth century they became scarce. (Overhunting, egg collecting, and development of wetlands were among the causes of the decline.) In the 1930s, efforts to restore their numbers led to government-sponsored releases of resident “giant” Canada Geese for hunting. Not long after, as lawns started to proliferate, many of these resident geese flocks began to thrive and expand their range. Though resident and migratory geese may mingle during winter, they retain separate breeding ranges and do not typically interbreed.

Now, even with hunting pressure to the tune of 3.2 million geese per year in North America, the resident population continues to grow. These hunting numbers combine migratory and resident birds—it’s often hard to separate them out on their wintering grounds. But most biologists believe there are far too many resident geese—more than can be sustained in urban-suburban areas.

Few Curbs on Population

Resident Canada Geese have adjusted well to living near people, with few significant curbs on their numbers. Resident geese in cities and suburbs are safe from most predators, many people like to feed them, and they are less vulnerable to hunting because they tend to live in settled areas where firearm restrictions often apply. By contrast, migratory Canada Goose populations are held in check by migration mortality, predation, late winter storms, and hunting. Resident geese begin nesting at a younger age and produce larger clutches than migratory geese. It’s no wonder their numbers are rising so fast.

As a result, it’s the resident birds that typically cause crop damage and provoke public nuisance complaints—which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says are at an all-time high and increasing every year.

Conflicts With People

Canada Geese are one of the few bird species that can digest grass, so they do well on the large expanses of lawn in parks, backyards, golf courses, farm fields, and airports. Resident geese have also overrun most native wetlands in the East, including the National Wildlife Refuges that were created to protect the migratory populations, as well as the diversity of other native wetland species. Aviation safety is a concern, too. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) estimates there are 240 goose-aircraft collisions each year nationwide, though some of these (like the flock that in 2009 notoriously caused U.S. Airways flight 1549 to go down in the Hudson River) can be traced to migratory birds.

There are also concerns about public health because goose droppings in water used for swimming or drinking may contain high coliform counts. The birds’ aggressive territoriality during breeding season may result in human threats or attacks. Droppings and overgrazing may create property damage, including erosion and reduced water quality in ponds.

What Can Be Done?

Canada Geese are a protected species under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. This protection applies to both resident and migratory geese. Neither individuals nor governmental entities may launch lethal control efforts without the proper federal, state, and (if needed) local permits. Finding out what rules and regulations apply is the first step, accomplished by contacting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (or Environment Canada) and your state’s wildlife agency.

Experts warn that no single management technique is going to be effective in deterring Canada Geese, and it’s vital to get buy-in from the community for whichever techniques are contemplated. The most commonly used techniques include preventing public feeding, altering the habitat to reduce its attractiveness to geese, hazing to scare geese away, using chemical repellents, hampering reproduction, and lethally removing the geese (for more information, see our list of resources at the end of this post).

The Cornell Lab’s Position

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s focus is to conserve and maintain healthy populations of native wild birds. Where warranted because of health or environmental concerns, we support humane efforts to reduce the overpopulation of resident Canada Geese. Because this problem is so widespread, often the only effective option is to use humane lethal methods such as suppressing reproduction or removing individuals. Geese are long-lived (some live more than 30 years) and in suburban areas closed to hunting, removal of breeding-age adults is one of the few effective ways to reduce population growth.

That said, we know firsthand how attached some people can become to individual birds or flocks in their neighborhoods. Not all communities may choose to reduce goose populations. But conflicts will only continue to grow if measures are not taken to curb the runaway growth of these birds.

Excellent resources exist to help you learn more about options for managing Canada Geese, including:

- Managing Canada Geese in Urban Environments: A Technical Guide – Cornell Cooperative Extension

- Management of Canada Goose Nesting [PDF] – USDA Wildlife Services

- Nuisance Canada Geese – New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (many states have produced their own similar resources)

- Management and Population Control of Canada and Cackling Geese in Southern Canada – Environment Canada

- The Humane Society of the United States offers resources including Solving Problems with Canada Geese [PDF] and Living with Wild Neighbors in Urban and Suburban Communities: A Guide for Local Leaders

(This post was edited on September 24, 2013, to clarify the Cornell Lab’s position on nuisance Canada Geese.)

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library